The Economist recently made the case that the United States economy is the envy of the world. American workers are exceptionally productive and innovative, and the corresponding increase in personal income and economic growth leaves “other rich countries in the dust.” Some education experts find this continued economic exceptionalism surprising because our students, on average, underperform on international tests.[1] But comparing average student test scores across countries obscures just how much cognitive ability the U.S. labor force possesses. Similarly, comparing average test scores across U.S. states masks the considerable talent in Ohio. That said, whereas the U.S. appears to put its talent to good use, Ohio struggles to retain its high achievers.

Harvard professor Paul Peterson and his colleagues (including Hoover Institution fellow Eric Hanushek) released an analysis in 2011 that illustrates just how variable student achievement is across the United States. They examined the test scores of U.S. eighth graders in 2007 (students who are helping to drive today’s economy) and compared them to the test scores of students across sixty-five countries participating in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA).[2] The U.S., on average, found itself near the middle of the pack in terms of its proficiency rates—on par with the U.K. and Italy in math—but states like Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and North Dakota stacked up quite well internationally. In math, Massachusetts ranked just ahead of Japan and Canada, and only six countries ranked higher (Singapore, South Korea, Finland, Taiwan, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland). Several U.S. states found themselves near the top in reading proficiency rates. Ohio wasn’t among the very highest-performing states, but still only eight countries significantly outperformed it in reading. When focusing only on average scores nationwide, we lose sight of states where students compete with the highest performers internationally.

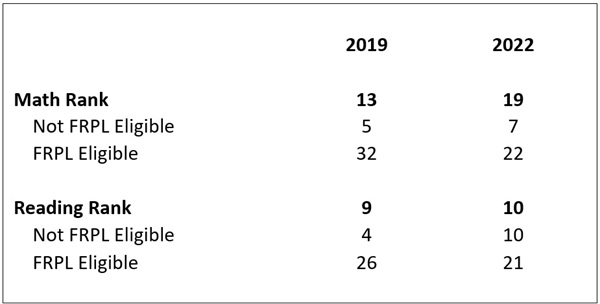

Comparing average test scores across states similarly obscures variation within them. Ohio’s average eighth grade test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) put it among the top twenty U.S. states in math and the top ten states in reading (both pre- and post-pandemic), but those respectable rankings obscure variation among Ohio students. For example, consider differences between students who are and are not eligible for free or reduced-price lunches (FRPL). Although Ohio ranks in the middle of the pack in terms of the math and reading achievement of its FRPL students, in both 2019 and 2022 Ohio ranked in the top ten for the achievement of its non-FRPL students. Indeed, Ohio may very well be in the top five—as it was in 2019 for both reading and math—due to our students’ impressive post-pandemic recovery in reading since 2022. (We’ll know more next calendar year, when the next round of NAEP results is released.)

Table 1. Ohio’s rank among U.S. states on eighth grade NAEP

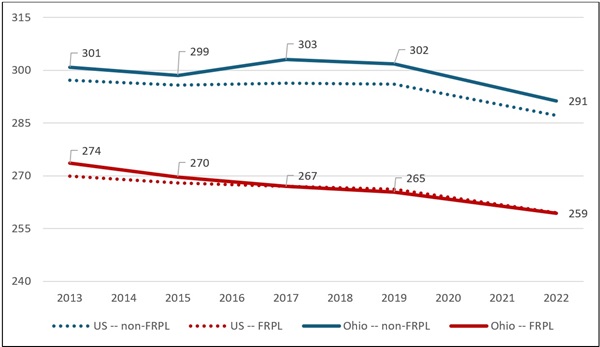

That the performance of Ohio’s economically disadvantaged students roughly tracks the national average is concerning. Indeed, the decline in Ohio’s average student achievement prior to the pandemic was driven entirely by Ohio’s economically disadvantaged students. As the figure below reveals, between 2013 and 2019, the achievement of non-FRPL students increased from 301 to 302, whereas the achievement of FRPL students declined 9 points, from 274 to 265 points. The results are similar for reading.

Figure 1. Math scale scores, eighth grade NAEP, U.S. and Ohio, by eligibility for FRPL

The precipitous decline in economically disadvantaged students’ basic skills threatens their futures, as the returns to numeracy skills are especially large in the U.S. We must make sure all families have high-quality educational options, particularly in Ohio’s largest school districts, in order to improve economically disadvantaged students’ achievement.[3] My recent evidence-based suggestions for addressing these test score declines, and Ohio’s current efforts to address chronic absenteeism, should go a long way toward reversing test score declines among these students.

Ohio’s large stock of high achievers

When it comes to the role of cognitive skills in driving economic growth, however, an important takeaway is that Ohio has a large stock of high-achieving students relative to other U.S. states. The roughly 50 percent of Ohio students who are not economically disadvantaged have, on average, remarkable levels of academic achievement in eighth grade—nearly on par with the highest-performing states of Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Washington, and just behind the national leader, New Jersey. Now consider the fact that Ohio is far larger. That means that Ohio is producing a large skilled labor force relative to other states. This is exactly the type of labor force that can help drive economic growth and the well-being of all Ohioans. Indeed, to the extent that the post-2012 achievement declines among economically disadvantaged students are due to out-of-school hardships following the Great Recession, promoting economic growth could itself be an important driver of future student achievement.

A top priority for Ohio policymakers should be talent retention. High-achieving Ohio students must be encouraged to obtain a college education in our state, as research indicates that students are likely to work where they attended college and that Ohio is a net exporter of four-year college graduates. That same research also indicates that those who attend selective colleges are most likely to leave their home state, which means the exodus from Ohio is even more consequential than the rates of out-of-state college attendance imply. Programs like the Governor’s Merit Scholarship for top Ohio students are a potentially important step in trying to retain Ohio’s impressive pool of skilled labor. Continuing to improve the state’s K–12 schools, paired with a focus on retaining Ohio’s remarkably high-achieving students, is a recipe for a bright future for all Ohioans.

[1] Indeed, in an effort to reconcile these facts, Mark Schneider recently argued that the U.S. may have reached some minimum floor of cognitive skills necessary for our dynamic economy to thrive, perhaps making it less urgent to improve those skills. This argument contradicts rigorous research that indicates that changes in average test scores are predictive of countries’ and states’ economic growth. A recent analysis of the implications of pandemic learning losses synthesizes this research and its implications in a concise and accessible way.

[2] They compare proficiency rates across countries and states by linking states’ scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) to scores on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). A prior report indicated that top U.S. states rank more poorly when it comes to the percent of students who score “advanced” in math. A recent report linked average test scores in this way based on the 2022 PISA. I do not focus on that linking here because of potential distortions caused by the pandemic. I also sought to compare the achievement of students who are currently in our labor force.

[3] Twenty-five percent of Ohio’s FRPL students are concentrated in Ohio’s ten largest school districts (Columbus City, Cleveland Municipal, Cincinnati Public, Akron City, Toledo City, South-Western City, Dayton City, Hamilton City, Canton City, and Springfield City), but most Ohio districts have a substantial share of such students.