During his terms in office, Governor Mike DeWine has been a strong supporter of public charter schools. His signature policy initiative in this area is the high-quality charter funding program that he shepherded through the legislature in 2019. The program has provided much-needed aid to charters, which have long faced significant funding shortfalls. A recent Fordham study found that qualifying schools have used these funds effectively—including increased teacher pay—and have yielded achievement gains for students.

Earlier this month, the governor unveiled his budget proposals for the next biennium. Included among them are several notable—and praiseworthy—charter school provisions that, if enacted, would continue to move the sector in the right direction. Let’s take a look at what three of his charter proposals would do.

1. Protect critical charter funding initiatives for the long-term

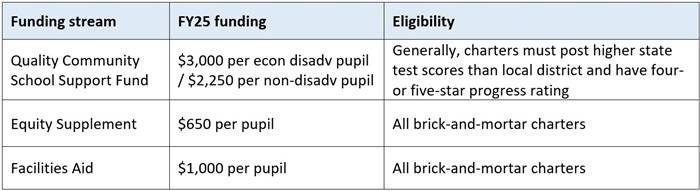

Over the past decade, state lawmakers have created three programs that help to narrow (though not quite erase) the charter funding gap. As table 1 indicates, they include the high-quality funds, as well as a charter equity supplement and per-pupil facilities allowance. Taken together, the high-quality funding and equity supplement narrow the operational funding gap for high-quality charters to about 10 percent below local district funding—a large improvement against the roughly 30 percent shortfall they have historically faced. Meanwhile, the facilities aid ensures that about half of charters’ building-related expenses are covered.

Table 1: State programs that narrow charter (community school) funding gaps[1]

Governor DeWine’s budget leaves all three programs intact and commendably raises the facilities amount to $1,500 per pupil. But it also takes one more important step forward that will help increase the likelihood that these programs continue long after the governor has left office. He proposes, for the first time, to etch these programs into statute,[2] a move that signals they are integral elements of the state’s funding system for charter schools. As such, it would be more politically challenging for future lawmakers to cut funding for these programs. As the budget bill heads to the legislature, lawmakers should approve the new statutory language. They should also further solidify the high-quality and facilities funds by incorporating those dollars into the state’s general K–12 education appropriation.[3]

2. Boost state support for charter facilities

Charters have long struggled to secure adequate facilities, as they’re ineligible for Ohio’s main school construction program and lack access to the local taxes that support districts’ capital projects. The only significant source of facility support for charters is the state’s per-pupil facility aid, which was first created during the Kasich administration. To its credit, the legislature has ramped up this funding in recent years. And as noted above, the governor has proposed another boost in his budget proposal.

House and Senate lawmakers should enthusiastically approve the per-pupil facility increase. They should also embrace proposed changes to the state’s unused facilities law that would increase charters’ access to vacant or underutilized district buildings. For years, Ohio has had a right-of-first-refusal law that requires districts to offer an “unused” building—either vacant or half-empty—to charters for lease or purchase. The policy makes perfect sense. These are purpose-built facilities that taxpayers have already paid for, and if provided to charters, they would continue to serve communities and students, rather than becoming blight or repurposed for other uses.

Unfortunately, school districts have not always dutifully offered these properties to charters, and the governor’s budget wisely strengthens this section of law to ensure they do so. His proposal includes a clearer and more objective definition of an “unused” facility, ensures that unused buildings are offered to charters at more affordable prices, opens opportunities for high-quality charters anywhere in the state to bid on facilities, and adds transparency requirements that help ensure compliance with these provisions. In sum, the proposed rewrite will help more charters meet their facility needs through increased access to unused district buildings.

3. Improve accountability for dropout recovery schools

Of Ohio’s roughly 320 charter schools, eighty-four are formally designated by the state as “dropout recovery” schools. To receive that designation, current law requires a “majority” of students to be enrolled in a dropout prevention and recovery program operated by the school. Acknowledging that most students attending such schools are academically behind, the state has implemented an alternative—and much softer—accountability system for dropout recovery charters.

However, the “majority” threshold (just 50.1 percent) for designation and alternative accountability allows dropout recovery schools to avoid the higher expectations that we should have for their general-education students. For instance, Ohio gives dropout recovery schools credit when students graduate well past the traditional four-year window after ninth grade.[4] That makes some sense for an adolescent who dropped out for a couple years, but that type of leniency is inappropriate for a general-education student who should be expected to graduate in four years. Also problematic is that a few dropout recovery schools currently serve elementary students. Their results simply go unaccounted for in the dropout recovery accountability system, which focuses on high school–based measures.

To its credit, the budget bill tightens the definition of a dropout recovery school. Under the proposed legislation, a dropout recovery charter must enroll only students ages fourteen to twenty-one who are at least one grade level behind their age cohort when they initially enroll.[5] In practice, this would mean that such schools are actually “specialized” dropout recovery high schools, and are more justly subject to alternative accountability standards. The bill provides a two-year transition period for current dropout recovery schools to allow them to create a “spin-off” school that serves students not covered in the age-range requirements, and to assist general-education students in finding another school.

* * *

To his credit, Governor DeWine has once again gotten charter policy off to a strong start in this year’s budget cycle. House and Senate lawmakers should enthusiastically approve the proposals discussed above. Yet they can move the ball even further downfield. As we at Fordham have recommended, they should further support charter facility needs by creating credit enhancement and revolving loan programs that reduce the costs of financing capital projects. They should also provide a lift to charters that do not qualify for the high-quality dollars—schools that still suffer from wide funding gaps—by boosting the charter equity supplement to $1,000 per pupil. In the days ahead, lawmakers should continue to make charters—a high-quality option for a growing number of Ohio families and students—a priority in the state budget.

[1] The governor’s budget proposal would provide STEMs with the equity supplement.

[2] In past budgets, these programs have been funded through temporary (i.e., “uncodified”) appropriations language of the budget bills.

[3] The high-quality funds and facilities aid are funded via standalone, line-item appropriations that could be vetoed by a future governor. The equity supplement is not funded via standalone appropriation.

[4] Dropout-recovery schools’ graduation rating is based on a combination of four-, five-, six-, seven-, and eight-year graduation rates. Other public schools’ (district and charter) graduation ratings are based on four- and five-year graduation rates.

[5] The bill also says a dropout recovery school may enroll students who “experience crises that significantly interfere with their academic progress such that they are prevented from continuing their traditional educational programs.”