Since taking office in 2019, Governor DeWine has prioritized expanding and improving career pathways. One of the benefits of a well-designed pathway is the opportunity for students to earn industry-recognized credentials (IRCs). Credentials allow students to demonstrate their knowledge and skill mastery, verify their qualifications and competence via a third-party, and signal to employers that they are well-prepared. IRCs may be prerequisites for certain jobs and can also boost earnings and employment.

Although Ohio has some room to grow when it comes to data collection and transparency, it does annually track IRCs at the state and district level. In this piece, we’ll examine a few takeaways from the most recent state report card.

1. The number of credentials earned by Ohio students is skyrocketing.

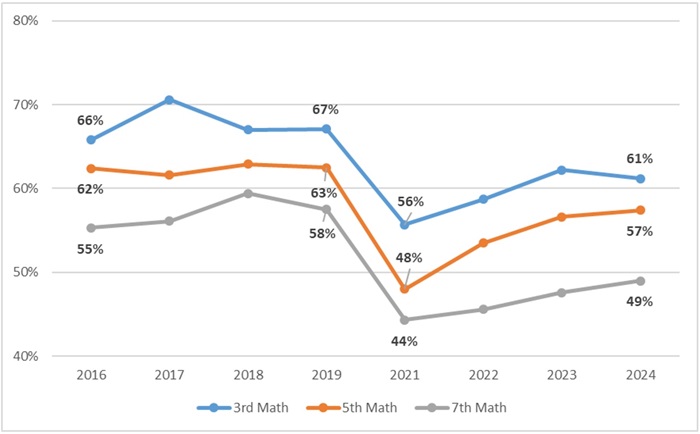

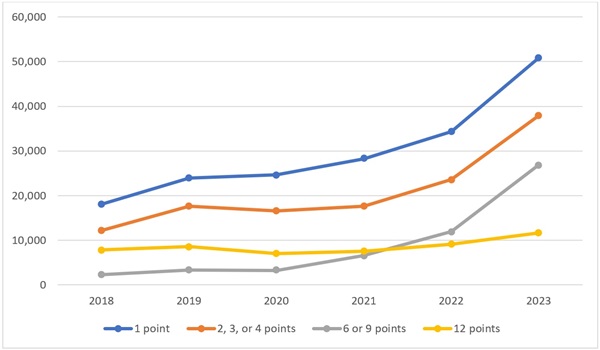

Over the last few years, the number of credentials earned has dramatically increased. Chart 1 demonstrates that between 2018 and 2023 the number tripled. The two most recent years, 2022 and 2023, represent a particularly steep incline.

Chart 1. Number of credentials earned statewide, 2018–2023

This credentialing surge can be attributed to several factors. First, state-funded initiatives like the Innovative Workforce Incentive Program—which was designed to increase the number of students who earn qualifying credentials in “priority” industry sectors—are likely having an impact. Second, Ohio lawmakers passed a revised set of graduation requirements in 2019 that made room for career pathways. Under these standards, students must not only complete course requirements to earn a diploma, but also demonstrate both competency and readiness. For the competency portion, they are permitted to meet standards based on career experience and technical skill, which can include earning at least twelve points in the state’s credentialing system (more on that below). For the readiness portion, students must earn at least two diploma seals. The Industry-Recognized Credential Seal is one of those options.

2. It’s unclear whether the most-earned credentials are valuable to students.

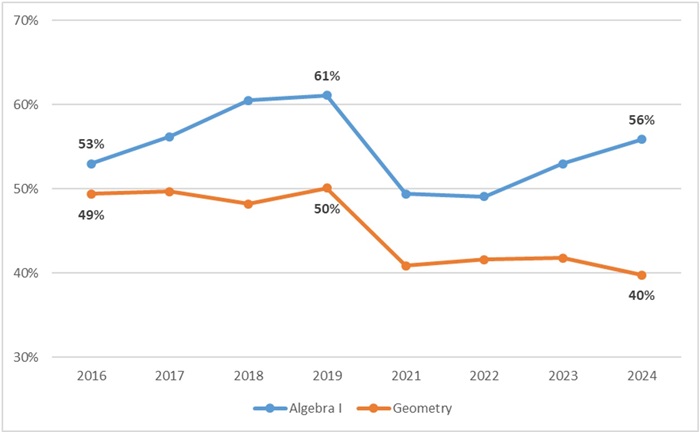

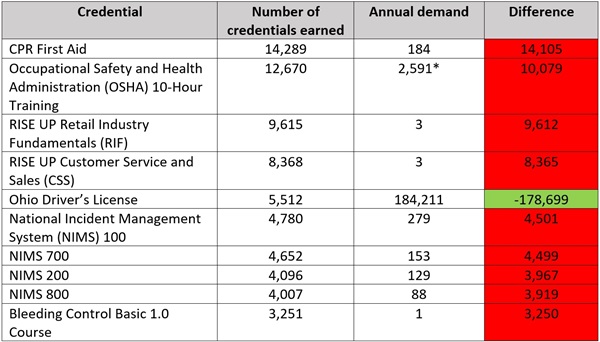

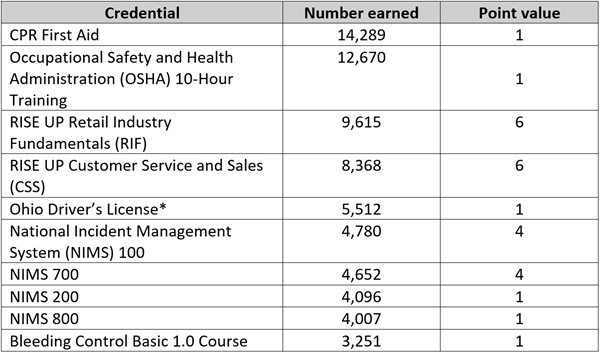

There are several ways to determine the value of a credential. One is by considering whether the state has identified it as valuable. In Ohio, credentials are assigned a point value between one and twelve. Point values are based on employer demand and/or state regulations and often signal the significance of the credential. For example, within the health career field, credentials like CPR First Aid or respiratory protection are each worth one point. In that same career field, a Certified Pharmacy Technician is worth twelve points. Unfortunately, as demonstrated by Table 1, none of top ten credentials earned by students in Ohio are worth twelve points. Half are worth just one point.

Table 1. Top ten credentials earned statewide 2023

*This refers to a state-issued basic driver’s license. It does not refer to a Commercial Driver’s License, which is worth 12 points.

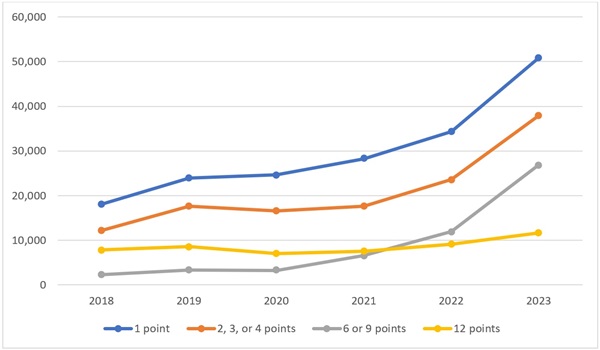

*This refers to a state-issued basic driver’s license. It does not refer to a Commercial Driver’s License, which is worth 12 points.The prevalence of one-point credentials isn’t a recent development. Chart 2 demonstrates that credentials worth one point have consistently been the most earned since 2018. Over the last six years, the number of twelve-point IRCs being earned hasn’t increased as rapidly as the number of one-point IRCs earned. And the gap between the two has grown each year. In 2018, the gap between one-point and twelve-point credentials was just over 10,000. By 2023, it had grown to more than 39,000.

Chart 2. Credentials earned statewide according to point value, 2018–2023

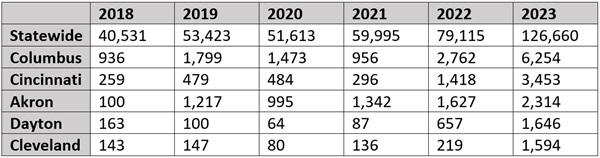

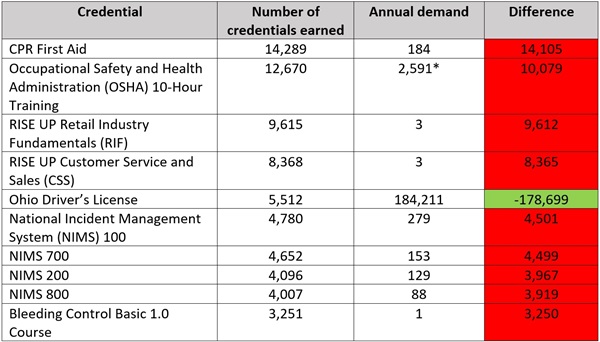

Another way to determine value is by examining employer demand. If employers are eager to hire graduates who possess a certain credential, then that credential is more valuable. But determining demand can be difficult, as employers often don’t signal which credentials are necessary for a job position, which are just “nice to have,” and which are irrelevant. A 2022 analysis of IRCs conducted by ExcelinEd and Lightcast attempted to offer some insight on employer demand by examining the average annual number of Ohio job postings that requested credentials over a two-year period (2020 and 2021). It’s by no means a perfect measure—it’s possible that employers value certain credentials even if they don’t mention them in job postings, and that some IRCs give students an unseen boost over other applicants. But until Ohio has better data, job postings are the easiest way to uniformly assess employer demand across the state.

Table 2 below identifies the top ten credentials statewide and how many were earned in 2023. Column three identifies the average annual number of Ohio job postings that requested each credential. Column four calculates the difference between recent supply (the number of credentials earned by the class of 2023) and previous employer demand. Red shading indicates that a credential is oversupplied, while green shading indicates an undersupply. With one exception—a state-issued driver’s license—all of Ohio’s most frequently earned credentials were not in high demand by employers. That should concern us.

Table 2. Annual demand for top ten credentials earned statewide

*This identifies the combined demand for OSHA 10-Hour and OSHA 30-Hour credentials. Even accounting for the potential extra demand of two credentials, the difference between supply and demand is negative.

*This identifies the combined demand for OSHA 10-Hour and OSHA 30-Hour credentials. Even accounting for the potential extra demand of two credentials, the difference between supply and demand is negative.A third way to consider value is through wages and salaries. Unfortunately, as is the case with employer demand, wages and salaries can be difficult to pin down. The aforementioned IRC report offers some insight. For example, although National Incident Management System (NIMS) credentials don’t have much annual demand, the postings that do request them have advertised wages above $50,000. But other credentials in Ohio’s top ten list—like CPR First Aid, OSHA 10-Hour, and RISE UP Retail Industry Fundamentals—don’t have advertised wages identified by the report. In other words, we don’t know for sure that students who earn these credentials end up in well-paying jobs. Going forward, it will be crucial for state leaders to follow through on linking education and credentials with workforce outcomes like wages.

3. Some districts are posting higher credential numbers than others.

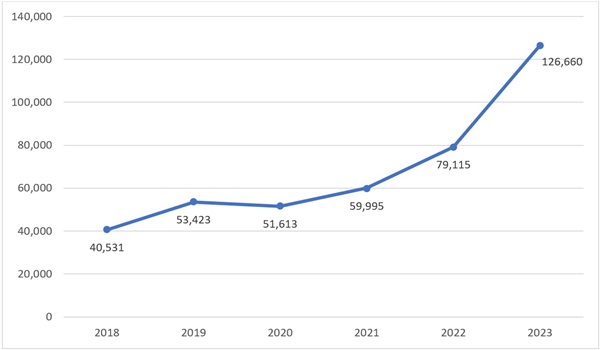

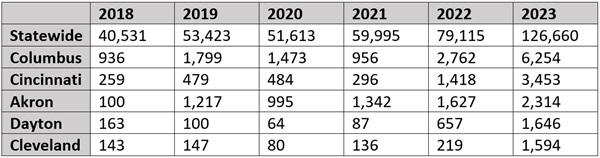

In 2023, the five districts with the highest number of IRCs were Columbus, Cincinnati, Akron, Dayton, and Cleveland. All five of these districts are in the Ohio Eight. Together, they account for nearly 9 percent of Ohio’s students and roughly 12 percent of the credentials earned statewide. Table 3 identifies credential earning numbers from the last six years for each district as well as the state.

Table 3. Number of credentials earned in selected districts, 2018-2023

Given that it’s the largest district in the state, it’s not surprising that Columbus posted the highest number. In fact, in 2023, the district made up nearly 5 percent of all credentials earned statewide. But there have been some pretty significant increases elsewhere, too. Akron, for instance, went from 100 credentials earned in 2018 to more than 1,200 the following year. Other districts, like Cincinnati, Dayton, and Cleveland, didn’t see sharp increases until 2022 or 2023.

These rapidly rising numbers raise some important questions. For example, what credentials did students start earning in Akron to account for such massive growth? Are Columbus students earning the same credentials in 2023 that they were in 2018? To find out, we compiled some additional tables that can be found here. They identify the top three credentials earned in each district between 2018 and 2023. The number of IRCs earned appears in parentheses. There are a few interesting data points to note.

First, Akron’s sudden surge is attributable to RISE UP credentials. Since 2019, students in the district have earned 2,529 Retail Industry Fundamentals credentials and 1,739 Customer Service and Sales credentials. Each of these IRCs is worth six points and can be earned in the same career field (business, marketing, and finance or hospitality and tourism), which means students can bundle them to earn a diploma. And yet, according to job posting data, neither credential is in demand by employers. Remember, it’s still possible that employers in the Akron area value these credentials. But we don’t know for sure. In a similar vein, we have no idea whether these credentials lead to well-paying jobs with advancement opportunities. Until Ohio directly links workforce outcome data to credentials, there’s no way to know whether Akron students who earned these IRCs are better off.

Second, Cleveland’s sudden increase between 2022 and 2023 is also attributable to RISE UP credentials. The district’s top credential during 2022 was Microsoft Office Specialist PowerPoint 2016, with twenty-one credentials earned. The following year, the top credential was Retail Industry Fundamentals (223 earned), followed closely by Customer Service and Sales (217 earned).

Third, in the last two years, an increasing number of Columbus students are earning credentials from the National Incident Management System. These IRCs account for the district’s top four credentials in 2023, adding up to a total of 2,913. That’s approximately 46 percent of the district’s 2023 total. Columbus isn’t the only district that’s championing these credentials, either. Cincinnati and Cleveland also had National Incident Management System credentials in their top three during 2022 and 2023.

***

Over the last few years, Ohio policymakers have prioritized improving career pathways. Expanding opportunities to earn an IRC has been a key part of those efforts. The good news is that more students than ever are earning credentials. The bad news is that it’s unclear whether the students who are earning those credentials are better off. Going forward, Ohio leaders must carefully consider how to ensure that students—and schools—are incentivized to focus on meaningful credentials that lead to well-paying jobs.