With his state of the state address, DeWine seeks to build on previous accomplishments

In early April, Governor DeWine delivered the second state of the state address of his second term.

In early April, Governor DeWine delivered the second state of the state address of his second term.

In early April, Governor DeWine delivered the second state of the state address of his second term. Unlike last year’s address, which covered a wide range of topics, this one focused almost entirely on issues impacting children.

Among the governor’s new proposals are a Childcare Choice Voucher Program for qualifying families, as well as revisions to the state’s early childhood education quality rating system. Several healthcare initiatives made the cut, including an effort to ensure students who need glasses can get them. The governor also offered his full support for a pending legislative amendment that would require all schools to adopt smart phone policies aimed at minimizing phone usage by students in the classroom.

Well into his second term, several of DeWine’s other key priorities aim to build on his administration’s prior accomplishments. The governor doubled down in three important areas—implementing early literacy reforms, expanding awareness of career pathways, and bolstering school staffing pipelines. Let’s take a look at each.

1. Implementing early literacy reforms

In last year’s state of the state address, DeWine previewed his administration’s plan to improve early literacy by going all-in on the science of reading, a research-backed instructional approach that emphasizes phonics and knowledge-building. Lawmakers were on board with his ideas, and last year’s state budget bill included a new framework for literacy instruction in Ohio schools. The budget also allocated nearly $170 million to help schools purchase high-quality curricula aligned with the science of reading and to support professional development for teachers.

Although implementation of this new framework is well underway, DeWine noted two areas where his administration will be pushing harder. First, he pledged that the state will provide quality-rated preschool programs with access to curriculum aligned with the science of reading. Doing so should help ensure that, just like elementary schools, early childhood education programs are using curricula and materials grounded in research.

Second, the governor implored leaders at Ohio’s colleges and universities to align their teacher preparation programs to the science of reading. Given that less than half of the state’s teacher preparation programs currently provide teaching candidates with adequate coverage of all five components of reading science (phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension), bully pulpit encouragement from the governor is critical. Last year’s budget included provisions that required colleges and universities to make this transition, but there has been notable pushback from some in higher education. Over the next year, the state will begin auditing elementary teacher preparation programs to ensure they are training teaching candidates in reading science. After this initial audit, programs will be reviewed every four years. Those that are found to be out of alignment will have one year to address audit findings before their program approval is revoked by the chancellor of the Ohio Department of Higher Education. With this context in mind, it becomes obvious that DeWine’s remarks weren’t just encouragement—they were a firm (and needed) reminder to schools of education that following the law isn’t optional, and they need to get started.

2. Expanding awareness of career pathways

Over the last several years, Ohio lawmakers have invested significant funding in career pathways, which aim to ensure that students are well prepared for what comes after high school. These efforts include expanding and improving career and technical education (CTE) programs, which benefit students by blending career training and academic coursework. Last year’s budget, for example, allocated $100 million toward CTE equipment upgrades and another $200 million for building and expanding classrooms and training centers. The majority of this funding has already been awarded, and should give thousands more students access to CTE programming.

To build on these efforts, DeWine used his state of the state address to call on lawmakers to tweak state law to require each student to have a career plan. He pitched this change as a “very simple fix,” as every Ohio student is currently required to have a plan for meeting diploma requirements and their post-graduation goals.

The governor is right that the act of changing the law will be simple. But effective implementation of this change will be far more complex. Many school counselors already report being overworked and vastly outnumbered by the students they serve. Most students are currently unaware of the options that are available to them. And though parents are eager to help, they may not know how. State leaders have laid some initial groundwork via recent communication initiatives and the creation of helpful online tools. But ensuring that every student in Ohio has access to the information they need to make an effective plan—as well as consistent support from knowledgeable adults who have the time and resources to help them—is a tall task. Lawmakers will need to carefully consider how to put this plan into action, so that it results in something useful to students and not simply a box-checking exercise.

3. Bolstering school principal pipelines

Last fall, Governor DeWine announced the creation of the Teacher Apprenticeship Program. Apprenticeship programs offer workers job-related classroom training and on-the-job learning experience under the supervision of an experienced mentor. This kind of clinical experience is crucial for teachers. The state’s new model will empower teacher preparation programs and K–12 districts to partner together and offer apprenticeships as an additional pathway into the classroom. It will largely be aimed at employees already working in schools—staff like teacher aides, librarians, and bus drivers—and is just one of several statewide initiatives aimed at bolstering the teacher pipeline.

In his state of the state address, DeWine acknowledged that teachers aren’t the only school employees who can have a big impact on kids. “Principals are vitally important to a school’s success,” he noted. “A great principal is the leader in the school, who creates the conditions for students, teachers, and staff alike to thrive.” With these impacts in mind, he announced that the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce would create a Principal Apprenticeship Program. Similar to the teacher apprenticeship, this new program will provide aspiring principals with “hands-on, in-school training that will better prepare them for the challenges of the job.” This isn’t the first time that state leaders have attempted to bolster the principal pipeline, so the devil will be in the details. But given the outsized impact that a principal can have on a school and its students and staff, the governor deserves kudos for acknowledging the importance of—and investing in—school leadership.

***

In last year’s budget, Governor DeWine and Ohio lawmakers invested hundreds of millions in education and passed policies aimed at improving opportunities and outcomes for children. Based on the recent state of the state address, Ohioans should expect this commitment to students to continue. Although implementation will matter immensely for each of the proposals outlined above, kudos to the DeWine administration for keeping kids front and center.

Ohio regularly creates and funds major education policies in a two-year biennial budget, so it’s never too early to start thinking about the 2025 cycle. This is the first of several posts where I’ll discuss issues that should be on lawmakers’ radars as they gear up. We open with one of the signature items from the last iteration: literacy reform.

Led by Governor DeWine, lawmakers passed landmark provisions that require Ohio schools to follow the science of reading—a research-based approach to reading instruction that emphasizes phonics and knowledge-rich curricula. Starting in 2024–25, elementary schools must use English language arts curricula aligned with the science of reading. They are also prohibited from using a debunked, though commonly used, method known as three-cueing, which encourages children to guess at words rather than sounding them out. The push for scientifically based instruction couldn’t come soon enough, as two in five Ohio students fall short of state reading standards.

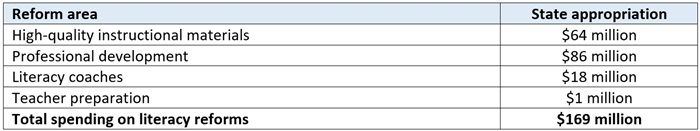

Recognizing the heft of these reforms, legislators wisely appropriated $169 million to support the overhaul. As table 1 indicates, the bulk of these dollars subsidize the purchase of new instructional materials ($64 million) and professional development that helps educators better understand the science of reading ($86 million). Another $18 million supports literacy coaches who provide more hands-on, intensive training in the state’s lowest-performing schools. Finally, $1 million is allocated to help teacher preparation programs transitioning to the science of reading. Of that amount, the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) receives a paltry $150,000 to carry out audits of preparation programs to ensure they align their training to the science of reading.

Table 1: Funding amounts for Ohio’s literacy reforms, FY 2024 and 2025 (combined)

Given the importance of literacy for individual students—and to Ohio’s future, more generally—legislators should stay the course on these reforms in the next budget cycle. They should continue to commit significant dollars for literacy, though also consider ways that update the uses of these funding streams as implementation progresses and schools’ needs evolve. Here’s a look at several ways legislators could target literacy dollars in the next biennium (note, the following mostly covers funding for the initiative, with less discussion on policy).

Thanks to the bold leadership of Governor DeWine and the 135th General Assembly, Ohio is on its way toward improving reading instruction. Yet the last budget was just the start—a down payment of sorts—and literacy should remain a focal point in the coming months, as well. Ohio’s 1.6 million public school students will be counting on state policymakers to keep the push going for reading instruction that promises higher achievement and greater opportunity in life.

[1] The previous budget requires DEW to collect information about district’s and school’s ELA curricula, but it does not require the agency to publicly report that information.

Last spring, state officials published data indicating that fewer young people are entering the teaching profession, teacher attrition rates have risen, and troubling shortages exist in specific grades and subject areas. In the weeks that followed, Ohio lawmakers took advantage of the biennial state budget to enact several policies aimed at addressing these issues. Their efforts included investing in Grow Your Own programs, making teacher licensure more flexible, and expanding the pool of substitute teachers.

These were welcome changes. But to ensure that Ohio has the teacher workforce it needs over the long haul, more changes are needed. In a 2022 policy brief—and a few other analyses on this blog—Fordham offered up some ideas. Let’s revisit three recommendations that could help boost the teacher pipeline.

1. Exempt out-of-state teachers from reading coursework requirements if they pass the state’s licensure exam on the first try.

Ohio offers teacher licensure reciprocity to out-of-state educators who wish to teach in the Buckeye State, but there are some limitations. For example, out-of-state teachers who wish to obtain a license in primary or middle childhood (grades pre-K–9) or any Intervention Specialist license must pass Ohio’s Foundations of Reading exam and complete twelve semester hours of reading coursework through an accredited college or university. In the past, applicants needed to complete at least six of the required twelve hours before being issued a license, though they were (and still are) permitted to apply undergraduate coursework toward the requirement.

The most recent state budget adjusted these coursework requirements for some out-of-state teachers. Now, applicants for a one-year, nonrenewable out-of-state license are not required to have completed at least six of the twelve required reading coursework hours if they pass the Foundations of Reading exam on the first try. That should make their transition to Ohio a little easier, as they can work to meet the coursework requirement while teaching on the temporary license. But they are still required to complete all twelve hours before they can advance or renew their license.

But requiring coursework at all—no matter how much—is a significant barrier, as taking these courses is expensive and time-consuming. That’s especially true for out-of-state teachers, who have already jumped through licensing hoops elsewhere. Passing the Foundations of Reading exam should be enough to signal that an out-of-state educator is qualified to teach literacy in Ohio. As such, lawmakers should allow teachers with valid out-of-state licenses who pass the exam on their first attempt to be exempt from all reading coursework requirements.

2. Allow out-of-state teachers trained by nontraditional programs to apply for a resident educator license if their training program has been approved by the state.

Ohio offers two pathways into the classroom for in-state teachers. The traditional licensure pathway requires candidates to complete a traditional teacher preparation program at a college or university and results in a resident educator license. The alternative licensure pathway requires candidates to complete a state-approved, nontraditional preparation program—known as an Alternative Licensure Institute—and results in an alternative resident educator license.

For out-of-state teachers, pathways into Ohio classrooms are based on experience. Educators with less than two years of teaching experience can apply for a resident educator license if they have completed an approved, traditional teacher preparation program through an accredited college or university. Teachers who have more experience—two full school years if they’ve completed a traditional preparation program, but three full school years if they haven’t—can apply for a professional license.

However, teachers who were trained in a nontraditional program but have less than three full years of teaching experience[1] must follow Ohio’s alternative pathway to obtain a license—which includes completing an approved Alternative Licensure Institute. This means that Ohio currently requires licensed out-of-state teachers (albeit those with less than three years of experience) to spend considerable amounts of time and money going through training that they’ve already completed in another state. On the one hand, this is a significant entry barrier for young and talented teachers who came to the classroom via nontraditional routes in other states. On the other hand, it ensures that relatively inexperienced teachers who were trained by nontraditional programs are exposed to the kind of pedagogical training that Ohio deems important.

Given the growth of nontraditional preparation programs nationwide—and the fact that not all of these programs are effective—lawmakers must walk a tightrope between widening the teacher pipeline and ensuring that educators who are granted licenses are well-prepared. One way to do so would be to require the Ohio Department of Higher Education to establish an approval process for out-of-state nontraditional programs. Programs that earn this approval would be granted license reciprocity that allows their teachers to apply for a resident educator license regardless of how many years of experience they have.

3. Bolster effective nontraditional teacher preparation programs.

The teaching profession hasn’t historically been friendly to career changers. Without a bachelor’s or master’s degree in education—and the time and money required to obtain them—it’s difficult to get into the classroom. Ohio could widen and strengthen its teacher pipeline if it offered high-quality programs that recruit recent college graduates and career professionals, train them, and then place them in public school classrooms.

Ohio data demonstrate that, although the number of newly licensed teachers coming out of universities has declined in recent years, the number of teachers coming from nontraditional pathways is rising. The numbers are still small—just 629 teachers in 2022—but nontraditional options are clearly appealing to more teacher candidates. Ohio leaders should pay attention and seize the opportunity.

They’ve already done so for one teacher training organization. State law currently includes a provision whereby participants in Teach For America (TFA) who meet certain criteria may be granted a resident educator license. This includes not only those who participate in TFA in Ohio, but also those who complete their TFA commitment in other states. In short, TFA is treated in the same manner as a traditional teacher preparation program that’s housed at a university, and TFA teachers earn the same license as their traditionally-trained counterparts.

However, TFA is the only nontraditional program that currently enjoys this privilege. There are other nontraditional programs that have been approved to train teachers in Ohio. But they must operate within the confines of the alternative licensure pathway. That means they must design or adjust their programming to fit within the parameters of an Alternative Licensure Institute (which candidates must complete to earn an initial license) and/or a Professional Development Institute (which candidates must complete to move on to a professional license, which is required to earn tenure).

This limitation could be why TFA is the only sizable nontraditional training program currently operating in Ohio. It’s the only one that isn’t required to adjust its existing model of pedagogical training to fit within the state’s parameters. Obviously, there are nontraditional programs that have been willing to jump through these hoops. But many of the established and effective nontraditional programs currently operating in other states might not be as willing to do so—and if their methods are producing effective teachers, they shouldn’t have to.

To widen teacher pipelines, state leaders need to make Ohio a welcoming place for as many effective nontraditional training programs as possible. As was the case with out-of-state reciprocity, this could be accomplished by establishing a process for nontraditional programs to gain approval through the Ohio Department of Higher Education to prepare participants for a resident—not alternative—educator license. Allowing nontraditional programs that can demonstrate the effectiveness of their methods to be treated the same as their traditional counterparts in colleges and universities could encourage the highly effective programs operating in other states to expand into Ohio.

***

Now more than ever, teachers matter. Students are still trying to catch up from pandemic-era learning loss. Achievement gaps remain stubbornly wide. And policies like Ohio’s science of reading initiative have the potential to improve outcomes for millions of kids. To address these issues, Ohio needs a strong pipeline of well-trained teachers. By implementing the recommendations outlined above, lawmakers could help make that happen.

A new report from the Hoover Institution’s Education Success Initiative provides another close look at the U.S. education system’s global standing in the aftermath of Covid, focusing specifically on the economic impacts the changes portend.

Analysts Eric Hanushek and Bradley Strauss compare Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data from before and after pandemic-related school closures and the temporary shift to remote learning. They show where American students as a whole landed in the achievement distribution, how international standings changed pre- and post-Covid, and conduct an interesting state-by-state analysis.

Hanushek and Strauss start with the most-recent administration of PISA, which tested the math, reading, and science skills of fifteen-year-old students in eighty-one countries and territories in 2022. To reduce noise in the data, comparisons are pared down to math results only. The United States ranked thirty-fourth among all participants, slightly below the mean score of the combined Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and comparable to Malta and the Slovak Republic. We are three-quarters of a standard deviation behind Singapore, the top performer internationally, and half of a standard deviation behind Macao and Taiwan—numbers two and three. While Singapore, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, and ten others actually showed a gain in PISA math results between 2018 (the last administration prior to Covid) and 2022, the United States was among the large cadre of countries that registered score drops: approximately 15 points. While not as steep as a number of others—Norway shed almost 35 points, Iceland nearly 40—Hanushek and Strauss calculate the economic impact of the drop on American students this way: The average student will have 5−6 percent lower lifetime earnings compared to expected earnings had there been no pandemic, unless something is done to fully remediate this learning loss. Absent such a fix, they calculate, the resulting lower-quality future labor force will cost the U.S. economy up to $31 trillion (in 2020 dollars)—equivalent to a 3 percent lower GDP throughout the remainder of the century.

2022 math results for NAEP, “The Nation’s Report Card,” are “transformed” by the analysts onto the same scale as PISA math results, creating a putative scale where individual states are ranked in comparison to PISA countries. The best-performing state on NAEP in 2022 was Massachusetts. It would be sixteenth in the world if it were ranked on its own, placing student performance just ahead of the average student in Austria and just behind the average student in the United Kingdom. The next-highest-performing state was Utah, ranking twenty-first between Slovenia and Finland. At the other end of the spectrum, thirteen states—including Oklahoma, West Virginia, Washington, D.C., and New Mexico—fell behind the average student performance in 77th-place Turkey.

Despite being the top state, Massachusetts was among those states registering more than a 10-point drop in NAEP math scores. Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Minnesota also registered scores more than 10 points lower in 2022 than in 2018. Fordham’s home state of Ohio was in the middle, dropping between 5 and 7 points overall and finishing just above Norway and the OECD average in the putative international rankings.

“The full explanation of the causes of the differential losses is not available,” Hanushek and Strauss write, “but there is evidence that hybrid and remote instruction related to closures contributed to the distribution of losses.” This becomes more obvious when we consider the widely varying Covid responses from different U.S. states. They then calculate the heterogeneity of impacts on average lifetime earnings—using their previous PISA-based methodology—in each state, finding a 4 percent loss for students whose states were at the top of the score distribution (like Massachusetts and Utah) and a whopping 9 percent loss for those at the bottom (such as Delaware and Oklahoma).

The silver lining around all this bad news is that these losses are not completely irremediable. Improved curricula, high-quality teaching, extended school days, and high-dosage tutoring have all shown promise in helping students catch up and accelerate back to where data indicate they should be. Hanushek and Strauss cite all these and more in their report. Unfortunately, here in 2024 (and even in 2022 when these state and international data were collected), time has already run out for older students, and some level of learning and economic losses have already been cemented into their futures. How many more students will leave high school before we can say we’ve done everything we can to help?

SOURCE: Eric A. Hanushek and Bradley Strauss, “A Global Perspective on U.S. Learning Losses,” Hoover Education Success Initiative (February 2024).

Across the country, schools are working to help students recover from pandemic learning losses. A new report, part of the Personalized Learning Initiative from the University of Chicago, examines high-dosage tutoring efforts and aims to provide some up-to-date evidence on how effective they’ve proven thus far.

The data come from four education agencies—three traditional districts and one state department of education—with which Initiative researchers partnered during the 2022–23 school year. These were chosen because they all implemented high-dosage tutoring programs in an effort to follow federal guidance “about how to deploy their ESSER dollars to overcome pandemic learning loss.”

The top-line findings are easily summarized: Tutoring can be implemented at scale and clearly boosts participating students’ end-of-year test scores. The overall impact on math scores is equivalent to about two-thirds of a year of learning, which would be enough to reverse the effects of pandemic learning loss for the average student. Reading test scores are generally positive but far less significant.

Breaking things down further, the analysts find that providing tutoring services during the school day is key to successful implementation. Two of the agencies studied—the New Mexico Public Education Department and an anonymous mid-sized urban district in California—both used out-of-school tutoring in 2022–23, with the former offering online services that could be accessed from home and the latter offering a formal afterschool program. Student participation was low for both programs (the California district didn’t even launch its tutoring until well after the start of the school year), and students who did participate saw minimal improvement in test scores compared to their non-participant peers.

The other two agencies—Chicago Public Schools and Georgia’s Fulton County Schools—focused on tutoring during the school day, and the report presents a detailed analysis of their efforts. Specifically, analysts followed 548 students from Chicago Public Schools and 1,506 students from Fulton County Schools. About half of the group from each school system was randomly assigned to receive high-dosage tutoring in math or reading in addition to classroom instruction, while the other half received classroom instruction only. Among the pooled sample from both districts, 76 percent of students assigned to tutoring participated in at least one session, and the average participating student took part in seventeen sessions. As noted above, data on reading test scores were considered “too noisy” to allow for conclusive evidence of impacts, but indicators were generally positive. Math impacts, however, were strongly positive across the board. The report cites additional factors that aided these outcomes, including having a consistent schedule, deploying well-trained and fully-supported tutors, and using a structured curriculum aligned with the school’s classroom instruction.

The bottom line here: High-dosage tutoring works and is still a powerful weapon to fight learning loss, especially in math. But the authors point out that all four of the education agencies relied on federal ESSER funding to pay for their tutoring programs. With that funding expiring by the end of September 2024, the current school year could be the last for many such programs, despite their demonstrated successes. Unfortunately, they have no recommendations for how to ensure funding support—the question of what happens to pandemic recovery efforts after the “fiscal cliff” is a vital one without clear answer—but their hope is that sharing these promising findings will bolster the case for continuation (and perhaps even expansion) with whatever funding sources can ultimately be found.

SOURCE: University of Chicago Education Lab and MDRC, “Realizing the Promise of High Dosage Tutoring at Scale: Preliminary Evidence for the Field” (March 2024).