Last year, Ohio lawmakers enacted bold reforms that push schools to follow the science of reading, an instructional method that teaches children to read via phonics and emphasizes background knowledge and vocabulary as pathways to strong comprehension. The overall package includes a requirement that schools use high-quality curricula aligned to the science of reading, with $64 million set aside for schools needing to purchase new instructional materials.

These provisions are critical, as research indicates that effective curricula can drive achievement gains. Unfortunately, literacy experts have warned for years that too many schools use curricula embedded with ineffectual methods, most notably three-cueing, a technique that prompts children to guess at words instead of sounding them out. Reporting by Emily Hanford has cast light on two programs notorious for three-cueing: Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study and Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell’s Classroom.

To better understand the curriculum landscape in the Buckeye State, lawmakers ordered the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) to survey districts and charter schools about their reading programs. A survey was fielded last fall and received near-universal response rates. Earlier this month, the department released the results, giving us insight into which programs were used during the 2022–23 school year. Schools were not required to use high-quality curricula that year, so this a “pre-reform” picture. The requirement to use materials from a state-approved list (which is nearing finalization) begins in 2024–25.[1]

What do we learn from this survey? The short answer is a lot—and stay tuned for more analysis in a forthcoming Fordham report. But here are the top five things to know.

Takeaway 1: Roughly half of Ohio districts will likely need to overhaul their reading curricula in the next year.

By my count, 285 school districts reported using a core reading curricula that is currently on DEW’s approved list.[2] This leaves 320 districts needing to purchase and implement curricula that meets state requirements by next school year. These districts reported use of disproven curricula like Classroom or Units of Study, or other non-approved materials. They also include districts that reported using only supplemental materials—an issue we’ll return to later—as well as the thirty-four districts using only district-developed materials.[3] Given the survey was based on what schools used in the 2022–23 school year, it’s possible that some districts moved towards state-approved curricula in 2023–24; others may be using state-approved core curricula but neglected to report it. Even with those possibilities, it still appears that roughly half of Ohio districts will need to purchase new materials. As noted above, state legislators wisely set aside funds to do this, and those dollars should be released to schools in the coming months.

Takeaway 2: Several state-approved core curricula are already commonly used.

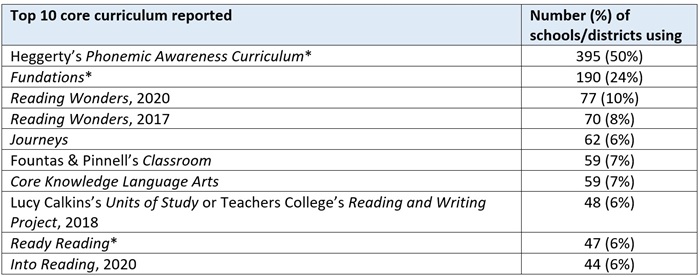

The key survey result is shown in table 1, which is direct from DEW’s report. It displays the ten most common responses to a survey question that asks schools about their “tier 1” (a.k.a. “core”) reading curricula for grades K–5.[4] When excluding three supplemental materials—noted by an asterisk and discussed in takeaway 5—we spot some good news, as a significant number of districts and charters use core materials already approved by DEW. These include McGraw Hill’s Reading Wonders with nearly 150 districts and charters citing use of one of its recent editions. Amplify’s highly-regarded Core Knowledge Language Arts program also cracks the top ten, with fifty-nine districts and charters using it, as well as Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Into Reading (forty-four). Another high-quality curricula, Great Minds’s Wit & Wisdom, narrowly missed the top ten with thirty-one districts and charters using it.

Table 1: Most commonly used reading curricula in Ohio, 2022–23

Takeaway 3: Dozens of districts and charters have been using ineffective curricula and will need to change course.

As for the bad stuff, we see that—again, excluding supplements—Fountas and Pinnell’s Classroom and Calkins’s Units of Study are the fourth and sixth most used core curricula in Ohio. Among districts, eight-eight of 605 used one of these two curricula (of these, seventeen reported both). Charter schools weren’t immune either, as twelve out of 222 elementary charters reported using one or both programs. To its credit, DEW has not approved Classroom or Units of Study. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Journeys is also a popular program, but isn’t on the state-approved list. To my knowledge, Journeys has not been associated with three-cueing but does receive low marks on EdReports’s evaluations.

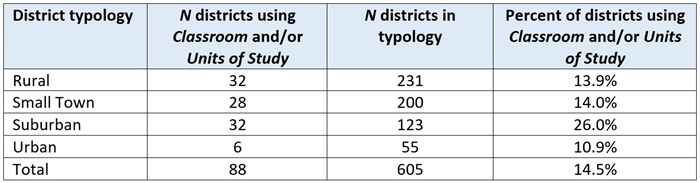

A closer look at the district-level results (available in a downloadable file) indicates that districts from all quarters of Ohio use Classroom and Units of Study. Yet suburban districts tend to use these programs more than others. This raises some dicey questions: Will affluent districts, which tend to have more political clout—plus higher test scores, given their demographics—push back on the new requirements? If so, how will policymakers respond? To head off potential grumbling, state leaders should be reaching out and reminding communities that all students—no matter their background—stand to benefit from effective reading instruction and strong, knowledge-rich curricula.

Table 2: Use of Fountas and Pinnell’s Classroom and Calkins’s Units of Study by district typology

Takeaway 4: The big-city districts are a mixed bag on reading curricula.

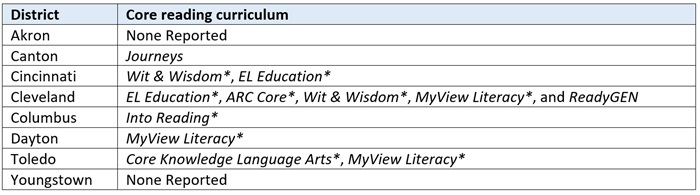

Students attending the Ohio Eight urban districts struggle most to achieve grade-level reading standards. It’s absolutely critical that their schools use effective reading curricula. The DEW reading survey finds signs of both hope and concern when we look at their programs. On the positive side, table 3 shows that Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo report using core curricula that has been approved by the state. On the other hand, Akron and Youngstown did not report a core curriculum—they only reported supplemental materials—while Canton reported use of the non-approved Journeys. These districts should use this opportunity to select highly-regarded programs such as Core Knowledge, EL Education, or Wit & Wisdom, as several of their urban counterparts have already done.

Table 3: Core reading curricula used by the Ohio Eight urban districts

Takeaway 5: Materials categorized as supplemental were confusingly cited as core reading curricula.

As evident from table 1 above, Heggerty’s Phonemic Awareness and Wilson Language Training’s Fundations topped the list of reading curricula used in Ohio schools. But there’s a catch. Neither are core curricula—despite the table’s title—and neither is Ready Reading, which appears further down the list. Instead, all three are supplemental materials that provide extra support beyond the core reading curriculum.[5] In fact, most (though not all) districts citing use of Phonemic Awareness and Fundations report using another core curriculum. Thus, if one follows the main table in the DEW report, a somewhat distorted picture of curricula emerges, as hundreds of districts reported supplements as core materials.

* * *

With survey results in hand, we now have a sense of just how heavy the science of reading implementation lift will be. For some, it might be relief that only half of districts require a curriculum overhaul. It could’ve been worse! Yet it’s still a tall task to order hundreds of schools to change course. Despite the challenge, state lawmakers are right: There’s no reason for schools to continue using disproven reading curricula. The stakes for children are too high.

[1] DEW’s current list of approved reading curricula is available here. Appeals are still being processed, and a final list is expected at the end of March.

[2] In its coverage of the survey results, Cleveland.com mistakenly reported that 93 percent of districts use materials that are on DEW’s list. That percentage is the number of districts reporting use of any type of published curricula (as opposed to district-developed), regardless of whether it’s on the state-approved list.

[3] On the charter school side, sixty-eight out of 222 elementary charters reported use of a state-approved core reading curricula.

[4] The exact wording was: “During the 2022–2023 school year, which K–5 English language arts instructional materials were primarily used by the district or school for Tier 1 instruction?”

[5] The Colorado Department of Education—a national leader in adopting high-quality materials—categorizes all three programs supplemental materials; DEW categorizes Fundations as supplement, while the other two programs do not currently appear on its state-approved lists.