‘Elected’ school boards and the dangerous illusion of democracy

By Aaron Churchill

By Aaron Churchill

This piece was first published on the education blog of The 74 Million.

William Phillis, the director of a lobbying group for Ohio’s school systems, recently stated in his daily email blast: “Our public school district is operated in accordance with federal, state and local regulations by citizens elected by the community....Traditional public schools epitomize the way democracy should work.” The email then went on to criticize charters for having self-appointed governing boards.

Setting aside charter boards for a moment, let’s consider the statement: Traditional public schools epitomize the way democracy should work. To quote tennis legend John McEnroe, “You can’t be serious.”

As observers of American politics would quickly point out, elections at any level of government aren’t perfect. One common concern in representative democracy is electoral participation. Approximately 40–50 percent of the electorate actually votes in midterm congressional races, and roughly 60 percent vote in presidential elections.

With only half of adults voting in some of these races, many have expressed concerns about the vibrancy of American citizenship.

But in comparison to school board races, national elections are veritable models of participatory democracy. In the fall of 2013, I calculated turnout rates in Franklin County school board races: Most turned out a measly percentage of registered voters — often less than 20 percent. (These rates would have skewed even lower had the entire voting-age population been used instead of registered voters.) Interestingly, during that cycle, Columbus citizens were not only electing school board members, but also deciding on a massive tax hike. And yet still, even with these seemingly critical matters on the ballot, only 19 percent of the electorate bothered to vote. Our friends at KidsOhio.org have noted the ongoing dismal turnout in Columbus, reporting in a policy brief that just 6 percent of adults voted in the spring 2015 school board primaries.

Paul Beck, a political science professor at Ohio State University, explained such low turnout rates, telling the Columbus Dispatch, “Voters are not really motivated to vote in these low-visibility contests.” Weak motivation is almost certainly a spot-on assessment. But further dampening public participation is the fact that in Ohio, school board elections are held “off cycle” — in non-congressional election years — when average voters aren’t paying attention to elections. Without the draw of high-profile candidates on the ballot, only the most attuned voters (or the most self-interested ones) participate in local school races.

Why don’t our champions of democracy, including the likes of Mr. Phillis, rush in to decry the woeful participation in school board elections? At the very least, why aren’t they clamoring to move school elections on cycle to ensure that more citizens’ voices are heard? The answer boils down to stone-cold self-interest.

You see, low-turnout elections protect interest groups deeply entrenched in the public education system. Research by Stanford’s Terry Moe demonstrates that low turnout provides an opening for special interest groups — most prominently labor unions — to capture school boards. When studying California board races, Moe observes that district employees — those with an occupational self-interest in the elections — tend to vote at higher rates than average citizens. Depending on the district, school employees were 2 to 7 times more likely to vote than the ordinary citizen. Unsurprisingly, voting rates were especially high when district employees both lived and worked in the same district. In conclusion, he writes, “Low turnout gives the unions an opportunity to mobilize support and tip the scale toward candidates they favor.”

Capturing school boards is an important goal for unions, as they will ultimately negotiate a labor agreement with the board. Given a union-friendly board, unions should be able to win managerial concessions during collective bargaining. These could include higher salaries and favorable benefits, or job protections such as rules around employee transfers, reductions-in-force, dismissal, class sizes, and grievance procedures. The various rules specified in these labor agreements (sometimes running hundreds of pages) stifle school leaders who aspire to organize their schools differently — and potentially in ways that better serve the interests of students, parents, and taxpayers.

Advocates of elected boards may claim that self-appointed charter boards are much worse. They’ll say that non-elected boards could have an overly cozy relationship with school management. To be sure, that’s a legitimate issue, and it shouldn’t be tolerated. Recently enacted House Bill 2 in Ohio weakens conflicts of interest like this (for more, see here). It is worth pointing out, however, that some of our most highly respected civic institutions have non-elected boards: One could easily name any number of responsible organizations that have excelled without elected boards (the Cleveland Clinic, the Columbus Museum of Art, and the United Way to name just a few).

Whether a school has an elected or self-appointed board isn’t the decisive factor in organizational success. A few districts may indeed thrive on public engagement via popular elections. But low participation, local politics, and the union influence shipwreck many more elected school boards. At the same time, some charter schools have smart, hard-working boards (though others do not). When it comes to school boards, what matters most is the character of those who serve — not how they were selected.

Management sage Peter Drucker once said, “If you want something new, you have to stop doing something old.” In recent years, policy makers have turned the page on Ohio’s old, outdated standards and accountability framework. The task now is to replace it with something that, if implemented correctly, will better prepare Buckeye students for the expectations of college and the rigors of a knowledge- and skills-driven workforce.

While the state’s former policies did establish a basic accountability framework aligned to standards, a reset was badly needed. Perhaps the most egregious problem was the manner in which the state publicly reported achievement. State officials routinely claimed that more than 80 percent of Ohio students were academically “proficient,” leaving most parents and taxpayers with a feel-good impression of the public school system.

The inconvenient truth, however, was that hundreds of thousands of pupils were struggling to master rigorous academic content. Alarmingly, the Ohio Board of Regents regularly reports that 30–40 percent of college freshman need remedial coursework in English or math. Results from the ACT reveal that fewer than half of all graduates meet college-ready benchmarks in all of the assessment’s content areas. Finally, outcomes from the “nation’s report card”—the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—indicate that just two in five Ohio students reach a rigorous standard for proficiency in math and reading.

To rectify this situation, policy makers across the nation have lifted standards. While Ohio leaders have been guiding the transition for several years, the 2014–15 school year marked a major turning point. It was the first year for next-generation assessments that match Ohio’s new learning standards; in spring 2015, the PARCC consortium’s exams in English language arts (ELA) and math were administered in Ohio and several other states.[1] Coinciding with these new exams, policy makers also raised cut scores—the minimum score needed to be deemed proficient—in order to more honestly relay how many students are mastering the content of the state’s new academic standards.

Of course, progress is rarely simple and often tumultuous, and last year’s assessment reboot posed several difficulties. They included concerns about the amount of time spent on testing, the transition from paper and pencil to online testing, and the impact of “opt-outs” on policies linked to exam results. Meanwhile, as a result of higher cut scores for achievement, school grades on a few key measures naturally fell statewide. Having foreseen these challenges, both technical and political in nature, Ohio lawmakers instituted a policy known as “safe harbor—a short-term reprieve on the formal consequences tied to performance on state exams. As the assessment environment solidifies, the state will lift safe harbor, starting with the 2017–18 school year.

Ever since 2005, we at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute have analyzed the results of Ohio’s school report cards. This year’s analysis provides a first look at student achievement in this new—and still unsettled—era of heightened academic standards. We offer three observations. (Stay tuned for the full report, to be released on Wednesday, for the nitty-gritty detail.)

First, although Ohio raised its standard for proficiency, its new cut scores still do not yield a completely honest view of college and career readiness. Figure 1 displays a comparison of NAEP proficiency in Ohio, the state’s proficiency rate on the 2014–15 assessments, and the statewide college and career readiness (CCR) rate, using the definition adopted by the PARCC consortium.[2] Ohio policy makers still overstate the number of students who are meeting rigorous grade-level targets in math and ELA when they report 60-percent-plus proficiency.

Figure 1: Statewide student achievement on 2015 NAEP and 2014–15 state exams

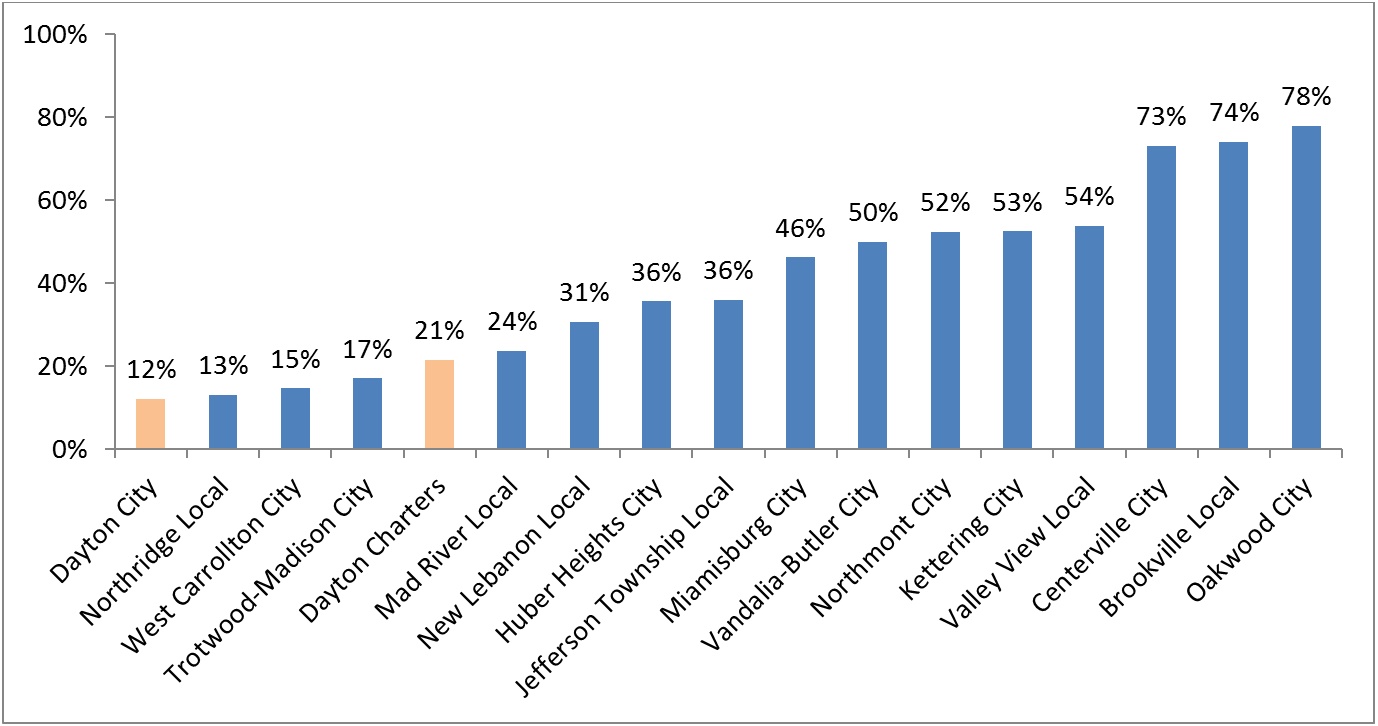

Second, when digging deeper into the state CCR results, we see the staggering inequities in educational outcomes. To be sure, education researchers have detected a wide achievement gap between historically disadvantaged students and their peers since the 1960s, but when using a rigorous gauge of student achievement, the gap appears all the more scandalous. There are several ways to portray inequity in student achievement, but consider the chart below. It displays the CCR rates in Fordham’s hometown of Dayton and its neighboring districts. We notice that in Dayton Public Schools (a high-poverty district), just 12 percent of students are on a sure academic path toward success after high school; meanwhile, upwards of 70 percent of students in a few of the region’s wealthy suburbs meet that same target. Worth noting is the fact that lagging achievement isn’t strictly endemic to Dayton; several poorer districts in the county—and the city’s charter sector—also have CCR rates under 25 percent.

Figure 2: CCR rates for Montgomery County public schools, eighth grade ELA, 2014–15

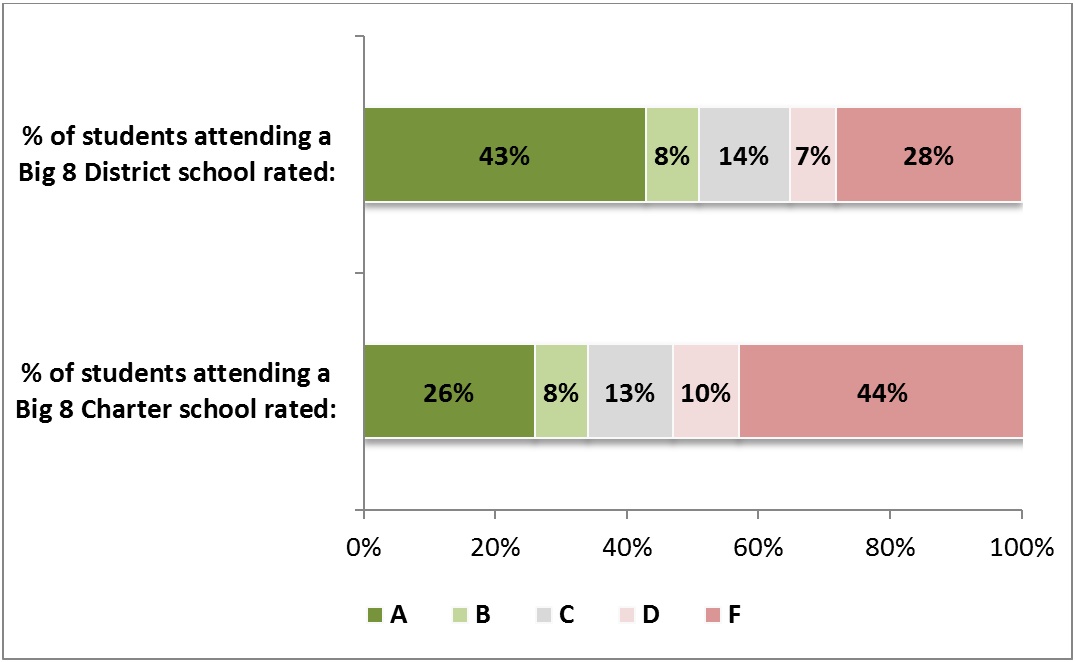

Given these troubling results, there is an acute need for outstanding high-poverty schools. But how many students have the opportunity to attend such schools? In our third and final observation, we note that a fair number of students do attend schools that are accelerating student growth (high value added), but many more enroll in schools that provide little to no growth beyond the norm. The chart below shows that the performance of urban schools on the value-added measure continues to be a mixed bag across both sectors. More than two in five students in the Big Eight districts attended an A-rated school, but one in five attended an F school. Among brick-and-mortar charter schools in the Big Eight, 26 percent of students attended an A-rated school, while 44 percent were enrolled in an F-rated school for value added.

Figure 3: Percentage of students enrolled in district versus charter school by its value-added rating, Ohio Big Eight, 2014–15[3]

* * *

What do these data all mean for policy makers and the general public? First, we must raise the level of discourse around achievement, and policy makers can aid in this task by continuing to ratchet up proficiency cut scores, as they’ve pledged to do. Not only is it a fundamental obligation of state officials to report honest statistics, but by providing an authentic gauge of whether students are on track for success after high school, parents and the public have the information needed to make course corrections before it’s too late. As Michael Cohen, president of Achieve, notes, “Parents and educators deserve honest, accurate information about how well their students are performing.…We don’t do our students any favors if we don’t level with them when test results come back.”

Second, the persistent inequity in educational outcomes must continue to be attacked in bold and perhaps unconventional ways. Happily, the report card data reveal scores of high-poverty schools that are making a difference in students’ lives (our organization proudly sponsors several high-performing urban charters). The public and philanthropic sectors would be wise to correctly identify top-notch urban schools and make aggressive investments in their growth and replication. At the same time, oversight bodies, which include school boards and charter sponsors, should consider permanently closing dysfunctional schools.

Like most states across the nation, Ohio has inaugurated a new era of education reform—one in which higher standards are de rigueur. And with a fresh start on federal education policy, states will have new opportunities to further sharpen their school reform policies in an effort to improve student learning. The work of reform isn’t finished. But at long last, in our small world of Ohio education policy, we can at least say for certain that the old has gone and the new has come.

[1] Starting in spring 2016, tests developed by the Ohio Department of Education and the American Institutes for Research will replace PARCC.

[2] Although Ohio did not officially release CCR rates, it is possible to calculate them; the consortium’s “met [CCR] expectations” is equal to the percentage of students who reach Ohio’s accelerated and advanced levels (levels 4 and 5 on Figure 1).

[3] Schools in the Toledo school district were not included, as their value-added results were not immediately released.

The “college preparation gap” among students graduating from high school is real and persistent. There are some signs that it has been stabilizing in recent years, but the fact remains that too many holders of high school diplomas aren’t ready for college-level work. Nowhere is it more apparent than in the realm of community college, where 68 percent of students require at least some form of remedial coursework (also known as “developmental education”) just to get to square one. Perhaps four-year colleges should face facts and refuse to admit students who aren’t ready, but we’re not there yet. For better or worse, community colleges have their doors wide open when it comes to “underprepared” students who still want to give college a go. But do they have their eyes similarly wide open? Two recent reports highlight the good, the bad, and the ugly among community colleges’ efforts to build successful students via remediation.

First up, a report from the Center for Community College Student Engagement (CCCSE) surveying approximately seventy thousand students from more than 150 of its institutions across the country. The vast majority (86 percent) of the incoming students surveyed believed they were academically prepared to succeed at their college, yet 68 percent of those same students reported placing into at least one developmental education class. Despite their belief in their own readiness, most who took the remedial placements indicated that the material was, in fact, appropriate for their skill level. The report cites the National Student Clearinghouse’s college completions report from late 2015, which showed that just 39 percent of degree-seeking, first-time-in-college students earn a degree or certificate within six years—with or without remediation. To combat these odds, CCCSE calls for a “remediation revolution” comprising a number of research-based options. One of those is greater collaboration with high schools (e.g., curriculum alignment, advising/mentoring, dual-credit offerings), with evidence provided from a very new program in the Goose Creek, Texas school district that aims to align education pathways from pre-K through college graduation.

Interestingly, new research in the current issue of the Journal of Higher Education also examines remediation in Texas colleges (six community colleges and two four-year colleges). Specifically, the research investigates whether the institutions’ Developmental Summer Bridge Program (DSBP) helped recent high school graduates in need of remediation increase their persistence in college, credit accumulation, and course completion. The DSBP included 4–5 weeks of accelerated instruction in remedial coursework, student supports, instruction in “soft skills” required for college success, and a $400 stipend for successful completion of the program. The control group was left to its own devices over the summer, and while many students took advantage of more traditional summer brush-up courses, most simply enrolled in the fall in their assigned remedial classes. The treatment group, meanwhile, showed only “modest positive impacts in the short term” from the intensive DSBP, all of which had dissipated in a year.

Since P-16 alignment is still an unproven strategy, and summer tune-ups like DBSP have barely registered effects, what else remains in the community college toolbox? CCCSE suggests three other strategies to bust the remediation boom. First is using multiple measures to determine placement for incoming students rather than a single test. Evidence for this one comes from North Carolina, which adopted the policy for all community colleges in 2013 (mandatory compliance is due in fall 2016). Davidson County Community College got a head start and has already seen fewer remedial placements and more student success in credit-bearing courses by using a mix of unweighted GPA and high school transcript data (especially in math courses/grades). A second strategy is eliminating “cold” sittings for placement tests. Washington State Community College in Marietta, Ohio mandates compulsory brush-up sessions for students before taking placement tests, and Passaic County Community College in New Jersey offers a sample online placement test and video tutorials to keep students from being surprised by the rigor of the test. Both schools have seen reduced remedial placements. Third is co-requisite remediation—that is, students simultaneously attending a remedial and a credit-bearing course in the same subject. No one’s talking about the cost of this—a common bugbear with remediation—but the data from a startup program at Butler Community College in Kansas is nothing to sneeze at.

As Pennsylvania State University’s Sean Trainor put it a while back, “Community colleges have been at the forefront of nearly every major development in higher education.” They are also the canaries in the coal mine of higher education, it seems, as the remediation boom is making an even bigger noise in the two-year colleges than in their four-year counterparts. Let’s hope that one or more of these efforts can dampen the boom for good.

SOURCE: Center for Community College Student Engagement, “Expectations Meet Reality: The Underprepared Student and Community Colleges,” February 2016.

SOURCE: Heather Wathington, Joshua Pretlow, and Elisabeth Barnett, “A Good Start? The Impact of Texas’ Developmental Summer Bridge Program on Student Success,” The Journal of Higher Education (March/April 2016).

The White House has selected Columbus, along with nine other cities, as a focus site for two newly launched campaigns to address and eliminate chronic student absenteeism. The first is the My Brother’s Keeper Success Mentors Initiative, the “first-ever effort to scale an evidence-based, data-driven mentor model to reach and support the highest-risk students.” The program will connect over one million students across the ten cities with trained mentors, including coaches, administrative staff, teachers, security guards, AmeriCorps members, tutors, and others. The second initiative is a multi-million-dollar parent engagement campaign through the Ad Council, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Education and the Mott Foundation, to “elevate the conversation about the devastating impact of chronic absenteeism.” The initiative will target K–8 parents through a campaign website with downloadable resources, billboards, and Public Service Announcements on bus shelters and in doctors’ offices and schools. Chronic absenteeism—missing more than 10 percent of a school year—is a strong predictor of low performance and eventual dropping out. Research shows that when at-risk students have caring adults in their lives, their likelihood of dropping out decreases. We’re pleased to see the campaigns’ selection of Columbus, a city whose district has the second-lowest attendance rate of Ohio’s Big 8 urban districts, and look forward to seeing how the initiatives unfold.

A new report from KidsOhio.org does a nice job of quantifying career and technical education (CTE) in Columbus City Schools. Ohio has invested heavily in CTE programs in the last few years, and while the structure is somewhat byzantine, CTE opportunities seem to be catching on among high school students. According to this report, in the 2013–2014 school year, 29 percent of all district juniors and seniors were enrolled in career education courses. Courses were offered in two dedicated career centers and nine traditional high schools. Additionally, students from thirteen other nearby districts took CTE courses in Columbus, as did a small handful of charter and private school students. While the district offered thirty-seven different programs, more than half of CTE students were enrolled in just seven of them: engineering science, health science, performing arts, job training coordinating, visual design and imaging, media arts, and business management. However, courses in several of the region’s most in-demand job categories were among the least popular (such as welding/cutting and programming/software development). It is important to note that one program—job training coordination—is especially designed for students with special needs, and it was the only one that was full. Best of all, the CTE path configured by Columbus is flexible enough to allow students to pursue other rigorous coursework through Advanced Placement, College Credit Plus, and early college tracks. The biggest takeaway of this paper is that much more could be done to let students know of CTE program opportunities—all but one CTE program had ample capacity— (especially for charter and private school students, should anyone at the district level have that inclination) and to help kids navigate into and through these courses.

In a previous post, I outlined the current landscape of teacher policy in Ohio and pointed out some areas in need of significant reform. The largest problem—and perhaps the most intractable—is teacher preparation. Despite consensus on the need for reform, some solid ideas, and an abundance of opportunities over the last few decades, schools of education have changed very little. Ohio is no exception, and many of the Buckeye State’s teacher preparation programs are in need of an overhaul. Here are a few recommendations for how policy makers and preparation programs in Ohio can start making progress in the impervious-to-change area of teacher training.

Rethink ways of holding teacher preparation programs accountable

Uncle Ben may not have been thinking of education when he said, “With great power comes great responsibility,” but the shoe certainly fits. Teachers have an enormous impact on their students, and it makes sense that taxpayers, parents, and policy makers would want to ensure that the programs entrusted with training those teachers are accountable for their performance. Ohio leaders recognize this and have already taken some tentative steps toward judging teacher preparation programs on the performance of their graduates. Unfortunately, those steps may not be headed in the right direction. In my previous post, I explained some of the drawbacks of the Ohio Department of Higher Education’s yearly performance reports that publicize data on Ohio’s traditional teacher preparation programs. While the reports are a great step forward in transparency, too many of the measures used—student learning objectives (SLOs), licensure test scores, the number of candidate field hours and a vague “satisfactory” rating for completion—aren’t effective at differentiating the great teachers from the not-so-great ones.

Finding better measures isn’t going to be easy. Two new reports (here and here) from Bellwether question whether it’s even possible to determine the effectiveness of teacher preparation programs. Bellwether’s work makes clear that the inputs many states use—admission standards, course content, teaching practice, and exam scores—often do not determine a teacher’s future effectiveness. A potential solution is to measure outputs instead—the effectiveness of program completers once they’re in the field. It’s an idea akin to school accountability in the K–12 arena: Give teacher preparation programs the freedom to design, select, and train as they see fit, and then hold them accountable for the results. Unfortunately, there’s conflicting research there too—especially for states that judge outputs based on teacher evaluation systems that typically rate all teachers the same. Ohio is one of those states (90 percent of teachers were rated in the top two categories in 2015), and finding solid measures for both differentiating teachers and linking them back to their preparation programs promises to be a heavy lift.

Rather than rushing to grade teacher preparation programs using data from the state’s required teacher evaluation systems, policy makers should fund and review high-quality research that examines how best to differentiate teachers. They should revamp the state’s teacher evaluation system into one that truly differentiates teachers and determine if those lessons can be applied to teacher preparation programs. They should examine the programs that received high rankings from NCTQ on their last teacher preparation report (here and here) and pilot parts of those models in Ohio preparation programs. They should also look to states like Massachusetts, which have taken a thoughtful but strong stance in this realm. While accountability for teacher preparation programs is important—and should eventually be a real, measurable component of the sector that considers both inputs and outputs—the Buckeye State must avoid rushing into labels and consequences until it makes certain that it is effectively differentiating teachers.

Empower K–12 schools to establish and influence teacher training grounds

It’s going to take time and careful consideration to change teacher preparation programs, but there are thousands of kids who can’t afford to wait for the right system to finally fall into place. What can be done in the meantime?

A recent case study from the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation examines how a few highly successful charter schools (High Tech High in San Diego; Uncommon Schools, KIPP, and Achievement First in New York; and Match Education in Boston) have created their own teacher certification and master’s degree programs. Each of these schools began their foray into teacher credentialing because they had trouble finding teachers whose “philosophies and methods” aligned with their own missions. In addition, they found that many of the teachers they hired lacked the skills to be immediately successful in the classroom. By creating their own teacher training programs, these schools were able to connect formal teacher education with what happens in actual classrooms. Though each program develops teachers based on its parent school’s mission, philosophy, and favored instructional methods, each one also includes a performance-based graduation requirement. As a result, these programs function like competency-based models.

Ohio’s charter school sector doesn’t have the best reputation, so it’s understandable that folks might shy away from allowing charters to train teachers. But as with other forms of education innovation, teacher training doesn’t have to copy and paste models without making adjustments—and charters don’t have to be the only ones taking part in innovation. The Cleveland Metropolitan School District has already done something similar with principal training through its Aspiring Principals Academy (APA), a program that was established in partnership with New York City’s Aspiring Principals Program. A recent report from Education First examined partnerships between school districts and preparation programs and offered recommendations for how to shape teacher pipelines through collaboration. Schools in Ohio—district and charter alike, perhaps through city-based reform groups—could even band together to create programs that serve both types of schools. The organizations highlighted in the case study did experience obstacles, but Ohio stakeholders could preemptively address these by creating a pathway for state licensure and accreditation approval and by helping (or even providing) revenue and cost structures that would allow for sustainable models.

***

The bottom line when it comes to teacher preparation is that everyone deserves better—the kids who must be taught, the candidates who choose to make teaching their profession, and the taxpayers who expect their schools to be staffed with well-trained, effective educators. Teaching is a complex and difficult job. Teacher training needs to change if it’s going to prepare candidates to deliver what real schools and kids will need, but that’s only part of the challenge. Stay tuned for a future deep-dive into the complexity of teacher preparation programs’ admission standards, state licensure requirements, and recruiting the best and brightest students to be teachers.

America’s schools are staffed disproportionally by white (and mostly female) teachers. Increasing attention has been paid to the underrepresentation of teachers of color in American classrooms, with research examining its impact on expectations for students, referral rates for gifted programs, and even student achievement. This paper by American University’s Stephen Holt and Seth Gershenson adds valuable evidence to the discussion by measuring the impact of “student-teacher demographic mismatch”—being taught by a teacher of a different race—on student absences and suspensions.

The study uses student-level longitudinal data for over one million North Carolina students from kindergarten through fifth grade between the years 2006 and 2010. The researchers simultaneously controlled for student characteristics (e.g., gender, prior achievement) and classroom variables (e.g., teacher’s experience, class size, enrollment, etc.), noting that certain types of regression analysis are “very likely biased by unobserved factors that jointly determine assignment to an other-race teacher.” For example, parental motivation probably influences both student attendance and classroom assignments. The researchers conducted a variety of statistical sorting tests and concluded that there was no evidence of sorting on the variables they could observe, and likely none occurring on unobservable dimensions either. All of which is to say that students’ assignment to teachers was likely truly random, thus enabling researchers to apply a causal interpretation to the findings.

The results for suspensions were stark: Having a teacher of a different race upped the likelihood of suspension by 20 percent, with the results for non-white male students assigned to white teachers accounting for much of the disparity. Having an “other-race” teacher increased the likelihood of chronic absenteeism (eighteen or more days missed) by 3 percent, with non-white males assigned to white teachers most likely to be chronically absent. (The study did not break out teacher data by gender. Nor did it control for student income levels.) Interestingly, there was no relationship between student-teacher racial mismatch and excused absences, but a small and statistically significant impact on unexcused absences, lending evidence to researchers’ hypothesis that absenteeism is caused (at least in part) by “parental and student discomfort with other-race teachers through symbolic effects of demographic representation.”

Suspensions, which reflect the quality of student-teacher relationships as well as the discretion exercised by teachers when determining consequences, might understandably be influenced by subconscious teacher bias. However, given that teachers generally don’t set school discipline policies, it seems worth examining the impact of racial mismatch between students and school leaders (or the staff most closely involved with discipline matters). Finally, the fact that being taught by an other-race teacher also impacts absenteeism is somewhat surprising, lending credibility to the paper’s assertion that “absences reflect parental assessments of their child’s school, classroom, and teacher.”

The study reminds us that teacher race matters, especially for male, non-white students who are disproportionately suspended (and, to a lesser extent, chronically absent). While it’s clear from this study and others that students might be inadvertently harmed by lack of diversity in the teacher workforce, it’s less clear what schools should do about it—especially our poorest and most low-achieving schools that may struggle to recruit and retain high-quality teachers of any race. Even so, for anyone concerned about the achievement and wellbeing of minority students, it’s a topic that demands our attention—and our action.

SOURCE: Stephen Holt and Seth Gershenson, “The Impact of Teacher Demographic Representation on Student Attendance and Suspensions,” Institute for the Study of Labor (Germany) (December 2015).