School boards matter. Indeed, in Fordham’s new report Do School Boards Matter? researchers found that knowledgeable, hard-working boards that prioritize student achievement govern higher-performing districts. Perhaps this is no surprise, particularly given the wide-ranging authority of boards. In Ohio, school boards’ statutory powers include prescribing curriculum, appointing a treasurer and superintendent, creating a school schedule, and entering into labor contracts with teachers. Meanwhile, we in Columbus have painfully observed what happens when a school board fails to exercise diligent oversight.

School boards, then, can be potent entities (or dismally impotent ones). But does anyone care about them?

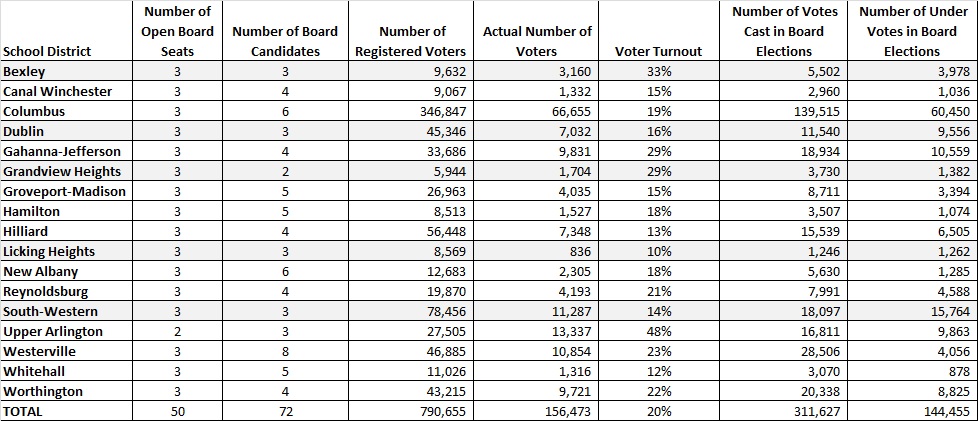

To dig into this question, I look at the November 2013 school-board elections for Franklin County. The county has a nice mix of districts, including one big-city district (Columbus) and a number of both high- and low-wealth suburban districts. I look at three data points: The number of contested seats, voter turnout rates, and “undervotes” among those who actually went to the polls. This slice of data portrays a general air of apathy among the electorate toward school boards.

First, when it comes to competition for seats, many of the seats went uncontested. Remarkably, there were just seventy-two candidates vying for fifty board seats across Franklin County—less than two candidates per open seat. In fact, five of the seventeen school districts had entirely uncontested races (the number of candidates equaled the number of open seats). If you ran for office in those districts, you automatically won. (There were no spring primaries either.) Six other districts had just one more candidate than open seats. The upshot: There seems to be scant interest in running for board seats and subsequently, little competition for them.

Second, the turnout for school-board elections is low, bordering on bleak. Ten of the seventeen districts experienced turnout rates less than 20 percent. As a point of reference, roughly 60 percent of Americans cast a ballot in presidential elections—and even then, there are groups working to increase voter turnout. True, some might consider it unfair to compare voter turnout in presidential elections to school-board races. But why not? A school board might actually have a greater influence—more than the president—in the everyday lives of the local citizens and their children. In a state where the “public common school” is vaunted and “local control” enshrined, the public’s indifference to school-board races (and other municipal ones) is jarring.

Third, as a result of few candidates relative to the number of open seats, there were a large number of undervotes (i.e., abstentions) among those who voted. Undervotes occur when electors use less than their full allotment of votes. For example, an elector might select just one candidate even though they are allowed to vote for three. Districts with uncontested contests experienced large numbers of abstentions; for example, Licking Heights, Bexley, South-Western, and Dublin all had nearly as many abstentions as actual votes. Why? In essence, their electors were given no choice in candidates. If you didn’t like (or didn't know) one of them, you had no other choice but to abstain. The amount of abstentions suggests the need to expand the pool of candidates: At least two candidates per open seat should be the norm instead of the exception.

Direct democracy works best when the body politic is engaged and the competition is fierce. But this slice of data suggests that people just don’t care about their school board. Meanwhile, too few people even bother to run for it. Maybe the data from this particular year and county is a fluke, but I doubt it. In response, Ohio could put school-board elections “on-cycle”—in even-numbered years—which would correspond with congressional and presidential elections. This is a sensible strategy in Ohio where elections are held off-cycle by state law. On-cycle elections would nearly certainly increase the number of votes cast in board races, and they might also attract more—and potentially stronger—candidates.

Or, maybe direct democracy just doesn’t work well if the creation of high-caliber school boards is the goal. Another viable alternative would be to scrap school-board elections entirely. Instead, mayors could be entrusted to appoint boards, a representative form of democracy that Cleveland and other big-city districts are experimenting with. At the end of the day, either solution, be it on-cycle elections or mayoral appointments, looks promising in light of the present—and stale way—of selecting school boards.

* * *

Table 1: Franklin County school board elections, November 2013

Source: Franklin County Board of Elections Notes: Shaded districts were uncontested races. Grandview Heights had a sizable number of write-in votes for its third open seat. The voting-age population in Franklin County was approximately 924,000 in 2013 according to the U.S. Census Bureau, indicating that “voter turnout” as a percentage of the voting-age population would have been lower than reported in Table 1.