Ohio’s superintendents and principals are ostensibly in charge of managing the operations of public schools. But, in reality, they typically have little latitude to do so. For many, their chief managerial constraint is that they are bound by the terms of collective bargaining agreements between school boards and district employees (“employee contracts”). These contracts, which can reach 300 pages in length, prescribe in exacting detail whom district leaders can consider for employment, what salaries and benefits they must offer, what workloads they can assign, how they must evaluate employees, and under what circumstances and in what manner they can attempt employee dismissals. They also often dictate far more than personnel management practices, imposing rules and procedures that prescribe how district administrators must make decisions on matters such as curriculum, student discipline, school closure, resource allocation, and testing.

Research (and common sense) tells us that binding the hands of public-school leaders in this way undermines their ability to meet the varied and evolving needs of students. If they lack the authority to manage personnel and make important decisions, then how much should we expect them to accomplish? It’s remarkable that superintendents and principals can move the needle at all when it comes to students’ academic outcomes. Indeed, research indicates that superintendents typically have a small impact on student achievement. A handful of rigorous studies reveal that principals can have a substantial impact on students’ academic and behavioral outcomes through their leadership and management of personnel and resources, but these studies draw primarily on data from a few states (especially Florida, North Carolina, and Texas) that were near the bottom in terms of union strength (and the likely restrictiveness of teacher contracts) around the time the data were collected.

The impact of superintendents and principals may be more muted in states that have strong public-sector collective-bargaining laws. But there is also significant variation in managerial discretion across states with strong bargaining laws. Research on teacher contracts in states with strong unions (California, Michigan, and Washington) indicates that the restrictiveness of teacher contracts varies significantly, even across districts within each state. Thus, regardless of whether schools operate in states with strong employee unions, the extent to which employee contracts restrict managerial discretion varies significantly.

How oppressive are districts’ employee contracts and how much does their managerial restrictiveness vary? Answering this question precisely is labor intensive. The most careful research on the topic coded 334 potential contract provisions for a sample of California districts, including 140 items related to benefits (e.g., do teachers get a bonus for having a doctorate?), 120 related to working conditions (e.g., the extent to which senior teachers control their building assignments), 46 regarding evaluations and grievances (e.g., whether teachers are exempt from performance evaluations), and 28 items related to association rights (e.g., the extent to which employees can take a leave of absence to conduct union business).

Fortunately, there is a more efficient way to code the restrictiveness of Ohio districts’ employee contracts. One can simply count the number of statements indicating that district personnel “shall” or “will” perform some action. After demonstrating that this proxy of contract restrictiveness is informative, I use the results of my analysis (which includes recently negotiated and currently active teacher contracts across 556 of Ohio’s 609 districts) to identify the fifteen districts with the most oppressive contracts. I conclude with a real-world illustration (courtesy of the Akron Education Association) of how such managerial constraints continue to directly harm Ohio’s most vulnerable students, as well as some hope that we can use this knowledge to push back and put kids’ interests first.

Measuring the restrictiveness of Ohio districts’ employee contracts

Scholars have tried a number of strategies to measure the extent to which laws and union-negotiated contracts restrict managerial discretion. The total number of pages or words in a contract are common proxies. The problem with these approaches, however, is that variation in word or page counts may be unrelated to contract restrictiveness. For example, contracts may have narrow margins (like a pamphlet), advertisements from union sponsors, introductory remarks from union representatives, and extensive appendices that provide forms or other information—all of which might drive up word or page counts without affecting a contract’s restrictiveness. Indeed, some scholars have expressed concern that word counts and length may largely reflect the idiosyncrasies of the legal and leadership teams that draft contracts, such as the language conventions that they use and their inclination to regurgitate state law. Finally, not all contract language is equally restrictive. A provision that describes employee dental benefits may not impede management as much as a provision that prescribes exactly how administrators must fill teaching vacancies.

It is for these reasons that two renowned scholars, Katherine Struck and Sean Reardon, precisely coded how each California contract they reviewed addressed 334 separate potential contract provisions. Due to resource constraints, in subsequent studies they coded a subset of forty-three provisions that explained the bulk of the variation in California contracts’ restrictiveness. Yet these resource-intensive studies revealed two important facts: 1) contract length can be a reasonable proxy for contract restrictiveness (at least when irrelevant text is removed); and 2) contract restrictiveness, if measured correctly, correlates with district size, as both are strongly tied to the strength of districts’ employee unions. I use these facts to generate and validate my easier-to-code measure of contract restrictiveness.

I requested from the Ohio State Employment Relations Board (SERB) every contract (for teaching and non-teaching employees) that Ohio boards of education agreed to between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2023.[1] Among these 2,000+ contracts, I identified all contracts that were active as of January 1, 2024; scanned them using Adobe’s optical character recognition (OCR) software; and wrote code that cycled through each contract and counted the number of times the words “shall” or “will” appeared.[2] These counts should roughly capture the number of provisions that restrict managerial discretion while sidestepping some of the drawbacks of using word or page counts, such as varying margins and the inclusion of text unrelated to contract restrictiveness.

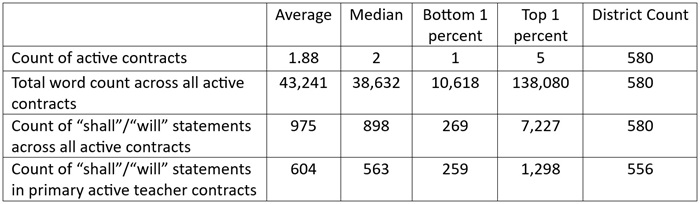

Based on the contracts SERB shared, I was able to generate measures of restrictiveness for the primary teacher contract (i.e., excluding contracts for particular types of teachers or for non-teaching employees) across 556 Ohio districts.[3] Table 1 (below) reveals that the typical Ohio district had two active employee contracts that contained 38,632 words and 898 instances of the words “shall” or “will.” In other words, the typical Ohio district’s contracts contain nearly 900 statements that likely restrict the managerial discretion of district leaders and administrators. The table also reveals that there is tremendous variation across Ohio districts in terms of the restrictiveness of the contracts they signed between 2019 and 2023.

Table 1. Number and length of active labor contracts in Ohio public school districts

To validate this measure of contract restrictiveness, I spot-checked a sample of contracts to confirm that these words primarily capture prescriptive statements, examined their frequency distribution compared to other words (like words such as “the,” “and,” and “a,” “will” and “shall” are often in the top ten of a contract’s most frequently used words), and correlated these counts with measures of district size, such as a district’s total residential population and student enrollment (correlations of 0.64 and 0.59, respectively). These correlations are comparable to those reported in the Strunk-Reardon study that coded 334 potential contract provisions.

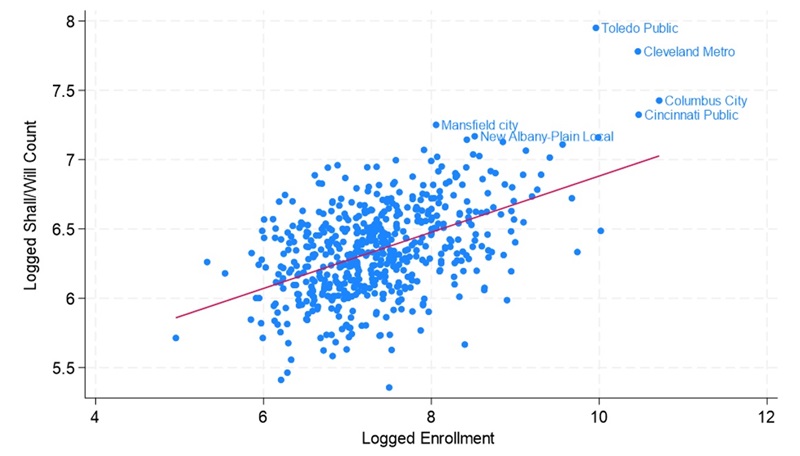

The figure below illustrates just how strong the relationship is between district enrollment and the count of “shall” and “will” in districts’ primary teacher contract. Although the axes are hard to interpret because the counts of restrictive provisions and district enrollments are logged (something that statisticians do so that very large districts with exceptionally restrictive contracts do not dominate the estimated relationship), the important takeaway is that there is a positive relationship between district size and my measure of contract restrictiveness. This fits the conventional wisdom among scholars that larger districts have more powerful unions and, thus, more restrictive contracts. Like the multi-state study I cite above, I found only a modest relationship between child poverty rates and contract restrictiveness. This suggests that restrictive contracts burden large districts regardless of wealth.

Figure 1. The relationship between district enrollments and the number of times a district’s primary teacher contract uses the words “shall” or “will” (restrictiveness proxy)

Which districts’ primary teacher contracts are the most oppressive?

In addition to demonstrating the relationship between district size and contract restrictiveness, Figure 1 reveals that some districts stand out. At the top righthand corner are the largest Ohio districts for which I coded contract data (Columbus City, Cleveland Metropolitan, Cincinnati Public, and Toledo Public). They have by far the most restrictive contracts. But some smaller districts (Mansfield City and New Albany-Plain Local) also jump out for having especially restrictive contracts.

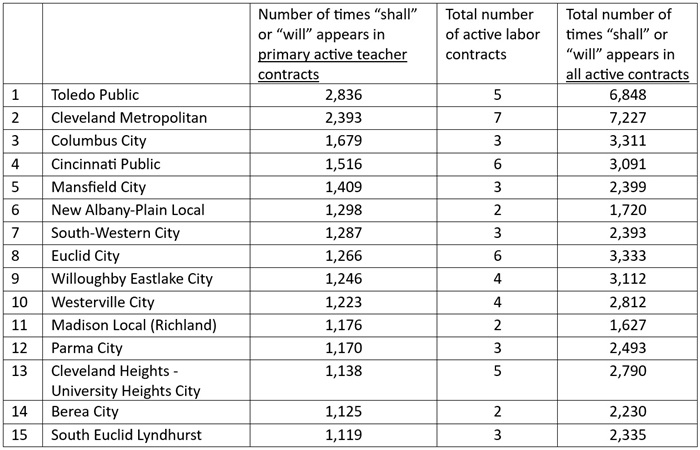

Table 2 provides a list of the top fifteen districts in terms of the restrictiveness of their primary teacher contracts, and it provides simple counts of restrictive statements containing “shall” or “will” (instead of hard-to-comprehend logged counts). By my measure, these districts’ primary teacher contracts are approximately 2–5 times as restrictive as the typical Ohio district’s contract. The gap is even bigger among the larger districts when one considers the total restrictiveness of all employee contracts combined (covering teaching and non-teaching staff).

Table 2. Ohio districts with the most restrictive active teacher contracts signed since 2019

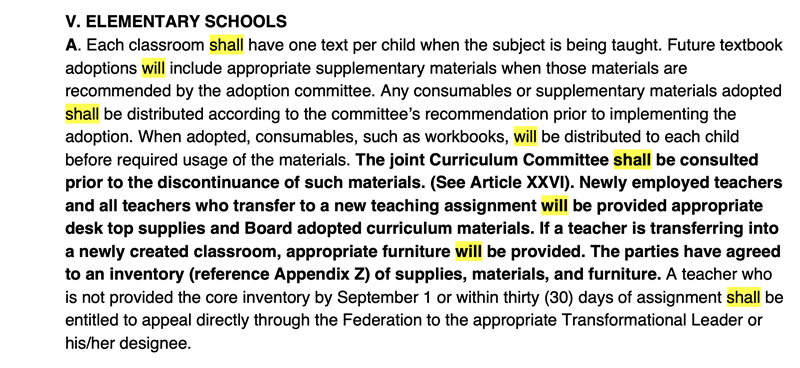

Those concerned about strengthening our public schools should skim the Toledo Public Schools contract to get a sense for how impossibly difficult (and likely soul-crushing) it must be to try to manage districts operating under such constraints. To provide an example, I simply scrolled to a random page (truly!) in Toledo Public’s contract and ended up on page thirty-six. I then selected the first paragraph just below the primary subheading on that page (to provide a bit of context as to the topic at hand). I have highlighted mentions of “shall” and “will” in yellow (bolded text is from the original):

These words may not capture every directive in the paragraph—particularly since the paragraph references content that is delineated elsewhere in the document—but the frequency with which “will” and “shall” appear suggests to me that those words serve as a reasonable proxy for how restrictive these sentences are for the leadership of Toledo Public Schools. Now, consider that these leaders are subjected to over 250 pages of this type of language. How large of an administrative staff does one need to even keep track of these rules and procedures?

The excerpt above reminds me of an old stereotype about government bureaucrats being primarily concerned with following rules and routines, as opposed to prioritizing the pursuit of public goals. Such rule-following is understandable, as it means that district leadership is less likely to be bogged down by employee grievances and political battles for having violated some contract provisions (perhaps inadvertently), but it also implies that they are likely less focused on the primary goals of public education.

Alleviating contract restrictiveness requires limiting union power

The “top fifteen” districts above are, by my measure, forced to operate under the most oppressive managerial constraints. But it is important to remember that contract restrictiveness is essentially a proxy for union strength. Larger districts have stronger unions (more dues-paying members means more resources and political power), and districts with stronger unions tend to negotiate contracts that are more restrictive (as Figure 1 illustrates). In other words, administrators who work in districts with restrictive teacher contracts are likely constrained by broader political dynamics, even if those constraints are not explicitly stated in teacher contracts. Indeed, research has documented how union strength—as captured by contract length, union revenue, district size, or the presence of collective bargaining agreements—is a key predictor of the sustained school closures that seriously harmed Ohio’s most disadvantaged students.

Remarkably, in spite of widespread awareness of teachers unions’ culpability in undermining the education of low-income kids during the pandemic and, therefore, contributing to expanding student achievement gaps, unions continue to exact harm on these students. For example, Akron Public Schools recently received a grant of $156,000 from the state to contract with a firm that would provide one-on-one tutoring to struggling readers—one of the few effective remedies for pandemic-induced learning loss. Because of union pressure, however, the superintendent felt compelled to ask the Akron Board of Education to rescind that contract. And how did the Akron Education Association exert this influence? By claiming unfair labor practices and filing grievances and lawsuits based in part on the terms of their collective bargaining agreement. (Unfortunately, Akron is one of the districts that had no active collective bargaining agreement in the files SERB pulled on December 31. I’ll try to have a full accounting of Ohio school districts in my next set of rankings. In the meantime, Akron Public’s seven employee contracts are available here.)

To alleviate the burden of oppressive union contracts, one must address unions’ political clout. One way to do so is for the state to limit what unions can bargain over. For example, as I discuss in a prior post, research suggests that prohibiting unions from negotiating rigid salary schedules (“step and lane” systems based on academic degrees and seniority) led to measurable gains in the effectiveness of Wisconsin districts, as district leadership was better able to recruit and retain effective teachers. Lawmakers could also prevent districts from waiving their management rights in collective bargaining negotiations, as my colleague Aaron Churchill recommends in his recent Fordham report.

Another way to address oppressive contracts is to limit more fundamental sources of union bargaining power in contract negotiations, such as their right to strike, their ability to raise money from district employees, and their ability to mobilize district resources for political gain. These sources of broad-based political power effectively enable unions to influence the election of school board members (and, thus, who will be on the other side of the table during contract negotiations), the outcomes of districts’ tax elections, and even the outcomes of state and federal elections and policymaking. As Terry Moe and Michael Hartney have convincingly and painstakingly documented, teachers unions have accumulated considerable political power and, using that power, in turn have secured policy changes that allowed them to amass yet more power.

Ultimately, countering teachers unions’ sweeping political influence is the best way to limit their hold on district management and provide district leaders some space to manage. But parents, taxpayers, district leaders, and other concerned citizens can only push back if they are aware of the problem. My simple measure of contract restrictiveness is meant to enhance this awareness by shining a light on just how oppressive union contracts can be and who the most egregious offenders are.

Stéphane Lavertu is a Senior Research Fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and Professor at The Ohio State University’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs or The Ohio State University.

[1] I limit the analysis to contracts taking effect after 2019 so that contract restrictiveness measures are roughly comparable, as the lengths of Ohio’s teacher contracts are increasing significantly over time.

[2] Fordham Institute President Mike Petrilli rightfully suggested other words like “must” could be good candidates. In the future, I hope to use a broader set of words and a more sophisticated algorithm to capture contract restrictiveness more precisely. Nevertheless, “shall” and “will” were the most common words in the set of contracts on which I conducted my original run.

[3] At least a dozen teacher contracts are not accounted for because I received them after running my program (which took several days), and a handful of others are missing because Adobe’s OCR could not generate readable files.