Last Thursday, Ohio released annual school report cards that offer parents and communities an objective review of the academic performance of its roughly 600 districts and 3,500 public schools. Much of the focus has understandably been on the “bottom line,” as this year’s reports included for the first time overall A through F grades that combine the many separate elements of the report card, much like GPAs do for students. In cities like Dayton and Columbus, the bottom-line F’s assigned to their school systems naturally made for depressing headlines.

Nobody should ignore or excuse the district-level results, as they speak volumes about the leadership and governance of those school systems—and about the often-challenging demographics of the children who fill them. But it’s also important to dive deeper and look at campus-level data. After all, children attend schools where education is actually delivered. It’s doubly important in Ohio’s major cities, as children have many school options—including public charters and district-operated schools—that vary widely in their report-card ratings. These differences are important for families to see and understand, as they should influence parents’ decisions about where to enroll their children. They’re also critical for civic and philanthropic leaders wishing to expand excellent high-poverty schools that narrow achievement gaps.

Let us, therefore, review the performance of district and public charter schools in Ohio’s “Big Eight” cities of Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown. Of the 260 charter schools that received A–F ratings, 197 were located in the Big Eight.[1] (This analysis excludes dropout-recovery charters which receive alternative report cards.)

When it comes to overall grades, the first thing to notice is that a number of individual schools in the Big Eight did much better than their districts. Although six of those districts earned F’s (Cincinnati and Akron were the exceptions with D’s), 26 percent of their schools earned a respectable C or above, and a handful received A’s and B’s. A similar story emerges for charter schools located in the Big Eight: 32 percent earned C’s or better. Among them are consistently high-performing elementary and middle charters, such as Columbus Collegiate Academy, as well as top-flight high schools like Dayton Early College Academy. (Both are authorized by the Fordham Foundation.) Considering that the average grade for a school in Ohio this year was a C, it means that these high-poverty schools are doing better than average, despite their more challenging demographics.

So there are bright spots, urban schools producing a solid education. But they are in the minority. What’s not as good is that about 70 percent of Big Eight schools received overall D’s or F’s (including a few that Fordham sponsors, as well).

Figure 1: Overall ratings for Big Eight district and charter schools

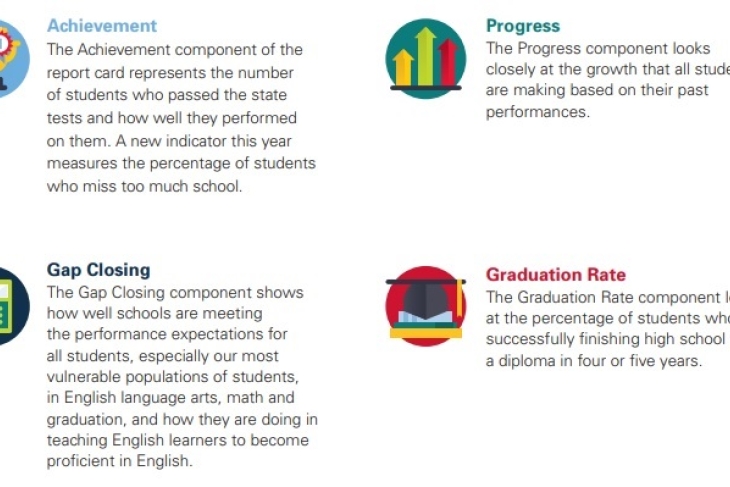

We can gain additional insight by turning to two key components of the Ohio report-card system: the overall value-added (VA) measure and the performance index (PI). For more than a decade, Ohio has used value-added statistical methods to gauge the impact that districts and schools have on student achievement when it’s tracked over time. This is what many refer to as “student growth.” Because value-added controls for students’ baseline achievement, the results on this measure are less correlated with poverty than measures of proficiency or graduation rates, so it’s key to understanding the effectiveness of individual schools and districts. Meanwhile, PI has long been used as a measure of overall student proficiency in a school, with greater credit being given when students reach higher achievement levels. The metric is essentially a weighted proficiency rate.

Figure 2: Overall value added ratings for Big Eight district and charter schools

As Figure 2 illustrates, 20 percent of Big Eight charters received an A on VA, as did 13 percent of district schools. The slight charter school advantage on VA ratings mirrors the results from the prior two years.

Although they are by no means conclusive, these encouraging results—sustained over multiple years—suggest that brick-and-mortar Big Eight charters may be moving the achievement needle a little faster than their district counterparts. But on a more sobering note, a majority of both district and charter schools received F’s on VA, indicating that many thousands of students are not making the growth needed to reach high achievement standards.

Figure 3: Performance index ratings for Big Eight charters and districts

Finally, let’s consider the PI ratings. Similar to years past Ohio’s urban schools perform poorly on this report-card indicator. Across the Big Eight, 92 percent of charters received a D or F, as did 90 percent of district schools. These ratings reveal again the achievement struggles of urban students who often come from less advantaged backgrounds and are falling short of performance benchmarks that, to Ohio’s credit, are more stringent than in years past. Yet these PI ratings still remain important to our understanding of urban school quality. All students, no matter their circumstances, should be expected to meet high academic standards, and should be provided with the supports necessary to do so. It’s critical to weaken the link between poverty and achievement—and this should remain one of the principal goals of education reform.

In summary, the results from the Big Eight are bleak. Seventy percent of urban schools received D’s and F’s as their overall grades. Roughly 90 percent are underperforming on the state’s performance index. And perhaps most distressingly, about 60 percent receive low value added ratings. Taken together, these figures indicate that lessening the challenges of poverty is hugely challenging. But it’s not impossible, as a few schools are beating the odds and helping students make the progress needed to reach high achievement levels. Those schools, both district and charter, are worth studying, emulating, and embracing.

***

Every year, Ohio’s school report cards elicit different responses—sometimes positive and sometimes negative. As we consider the results, it’s important to remember that the core idea behind report cards isn’t to cheerlead or denigrate schools. Rather, it’s to offer parents and communities objective reviews on the academic health of their local schools so that they can make better informed decisions and engage in productive ways. District-level ratings are a great place to start, but they don’t tell the whole story about education in a city or community. For that picture, we need to examine school ratings—and this year’s results show that, in the Big Eight cities, there are bright spots, but also many more areas for improvement within both the district and charter school sectors.