NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

In this article, we explore the most recent version of the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System (OTES) and how this legislative requirement holds out hope for transforming our state and our profession. The article is organized around the historical and legislative contexts that brought us to our current, third, version of OTES, the changes forthcoming, and next steps for our state that prides itself on improving instruction through standards-based conversations with teachers.

Historical Context

Ten years ago, then Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, proclaimed to millions of educators that due to the Recovery Act (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, 2009), almost $100 billion in new resources would be coming to schools and kids everywhere (Duncan, 2009). This statement was justified through data: “It tells us that something like 30 percent of our children, our students are not finishing high school. It tells us that many adults who do graduate go on to college but need remedial education. They're receiving high school diplomas, but they are not ready for college.”

Following this announcement, state educational agencies (SEAs) were encouraged to apply for competitive grants that would encourage our educational system to move toward a focus on college and career readiness. This grant process, known as Race to the Top (2009), was designed to spur and reward innovation and reforms in state and local district education through certain educational policies, including instituting performance-based evaluations for teachers and principals based on multiple measures of educator effectiveness in hopes of improving college and career readiness (USDOE, 2009).

Ohio Context

The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) was awarded a Race to the Top grant. In the application, ODE indicated they would “collaborate with Local Education Agencies (LEAs) and teacher unions to develop a teacher evaluation model that includes annual evaluations, provides timely and constructive feedback, includes student growth as a significant factor, and differentiates effectiveness using multiple rating categories. The development of a model evaluation system for teachers is a core initiative” (Strickland, Delisle, Cain, 2010).

Following the application and acceptance of funds, Ohio House Bill 1 directed Ohio’s education standards board to develop a model teacher evaluation plan and framework (NCTQ, 2011). Subsequent pieces of legislation, Ohio House Bill 153 and Senate Bill 316, required districts to design and revise their teacher evaluation protocols to conform with the state model. This system became known as OTES, the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. OTES was required under revised code to be implemented beginning the 2012-2013 or 2013-2014 school year, dependent on the expiration of local school district collective bargaining agreements.

The OTES Framework

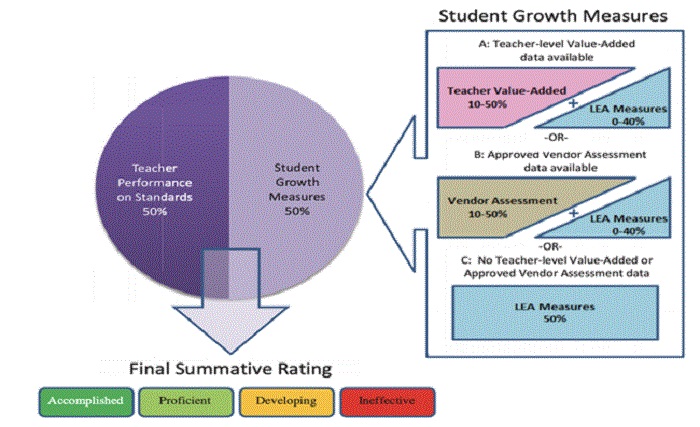

The original OTES was comprised of two components, as illustrated in Figure 1 (NCTQ, 2011): (1) a 50% performance rating determined by a holistic score on a rubric based on observations and walkthroughs; (2) a 50% student academic growth rating based on one of three measures dependent on the type of data available for a teacher (a) EVAAS (Education Value-added Assessment System) data where applicable for state tested areas; (b) Vendor Assessments approved by the ODE in non-tested areas; (c) local measures that comprise of Student Learning Objectives (SLOs) or Shared attribution, growth measures attributed to a district or group of buildings to encourage collaboration (see NCTQ, 2011, p. 8 for a detailed discussion of these terms).

Figure 1: Original OTES components, 2011

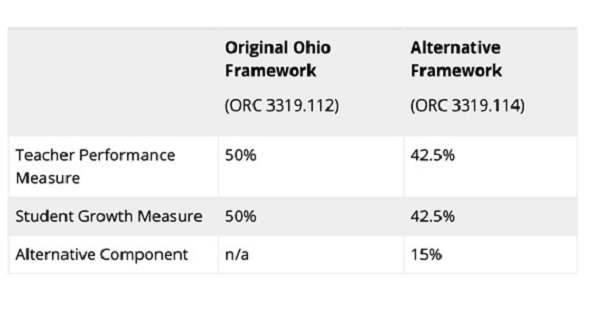

In 2014, following perceived concerns from the field regarding principals’ abilities to complete evaluations timely and concerns regarding the 50% attributed to student growth, the Ohio legislature passed Substitute House Bill 362. This reform bill allowed school districts with teachers who had high ratings to be evaluated less frequently, while still providing them with feedback on their work. Secondly, the bill revised the framework to offer school districts a choice between the original student growth measure structure and a new alternative structure allowing for 15 percent of the evaluation to be measured through student surveys, teacher self-evaluations, peer review evaluations or student portfolios, with the remaining portion divided equally between performance on standards and student growth measures. (See Figure 2 (ODE, 2017). Districts to this day have the ability, through collective bargaining negotiations, to choose one of the two frameworks.

Figure 2: OTES changes, 2017

What Does the Data Tell Us?

OTES was based on the belief that the education profession needed to improve preparation of students for college and careers. Given this system has now been in place since 2013 in one form or another, as Mr. Duncan decreed, what is the data telling us about this mission? Is our evaluation system helping teachers to prepare students for college and careers at better rates?

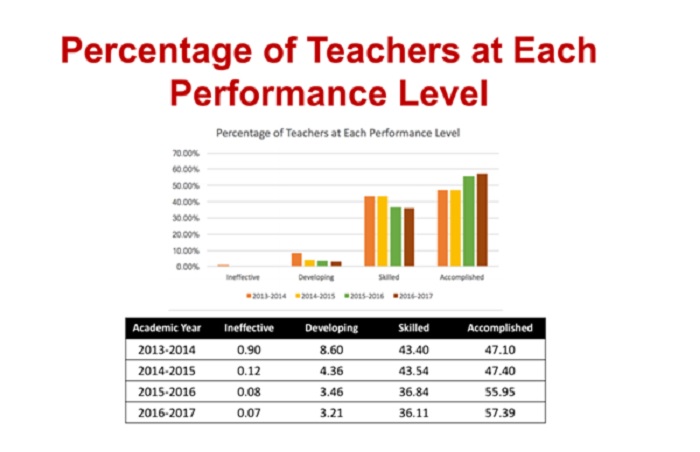

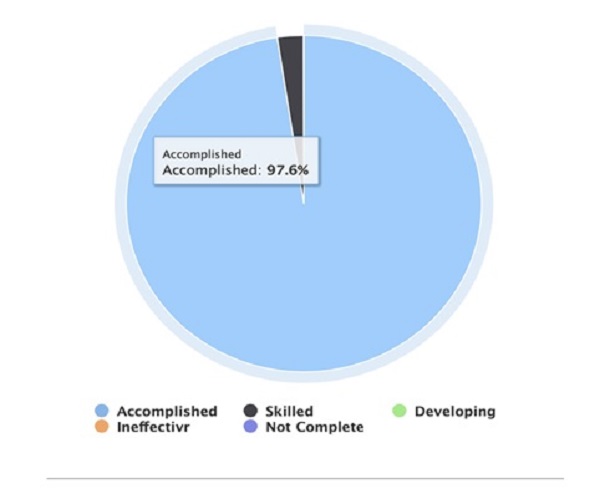

To answer these questions, two data sources are critical: the results of the OTES process and state achievement data. The OTES data is relatively simple: as explained in Figure 3, the majority of our teachers score at the highest performance level (accomplished), even from the program’s inception, and that number increases from year-to-year (ODE, 2019). This accomplished designation means “the teacher is a leader and model in the classroom, school, and district, exceeding expectations for performance” (NCTQ, 2013, p. 23) This is an interesting conundrum given the fact that the program’s own model indicates that the skilled (formerly known as proficient level) is “the rigorous, expected performance level for most experienced teachers” (p. 23).

Figure 3: Performance Level of Teachers in OTES

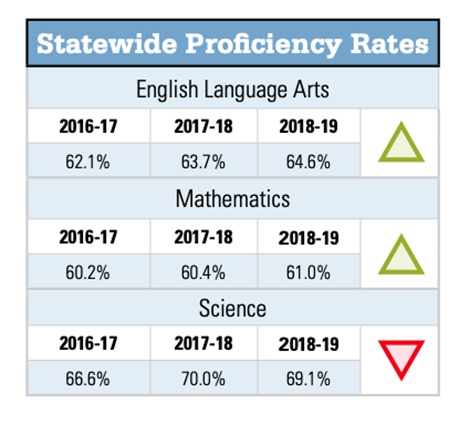

In relationship to student achievement data, growth from the report card shows achievement numbers are increasing as measured by state achievement tests in almost all areas. (See Figure 4. Some argue this is due to the relative consistency of assessment measures.

Others contend improved results indicate better teaching and improved dialogue with teachers about performance. Regardless of the interpretation, if achievement scores have increased, an argument can be made that the number of ratings for evaluation would increase and more teachers would be performing at higher levels (accomplished and skilled), which seems to be the case.

Figure 4: Statewide Proficiency Rates

What becomes interesting is what happens when the data is disaggregated by individual district. For example, the highest performing district (meeting 100% of the indicators and having the highest performance index in the state) has 97.6% of its teachers functioning at the accomplished level, and 3.4% functioning at skilled (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Teacher skill levels for highest performing district

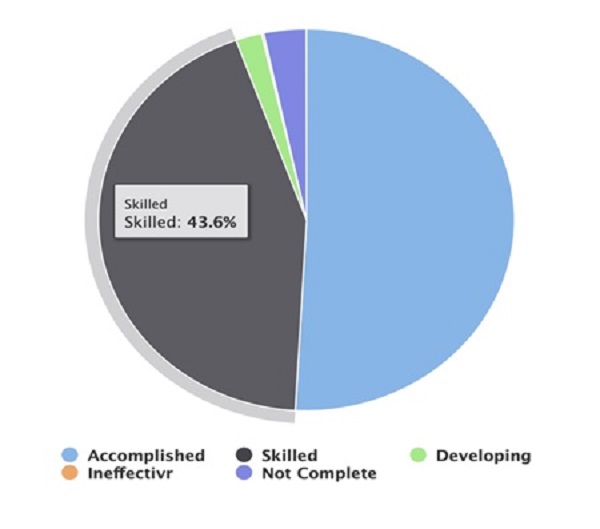

One would expect the same thing to happen at the low levels of the scale; however, this is not what happens. Take the district in figure 6 that ranks approximately 50th from the bottom of the 608 school districts in Ohio. The district earns 3 out of a possible 24 indicators met and scored a D on their performance index (64.5%). Yet, over 90% of their teachers perform at the two highest levels on the evaluation rubric.

Figure 6: Teacher skill levels for a low performing district

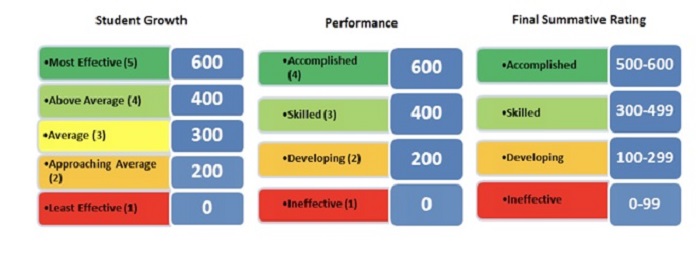

One would hope this would be an anomaly, but unfortunately the district is not unique! In several cases, there are district results whose achievement measures have decreased, and yet teacher evaluation ratings have increased! Possible reasons for this include the fact that due to the numerical conversion (as illustrated in Figure 7) in calculating the final summative rating for a teacher, it is possible for the less objective observation component to overshadow the student growth measure. Specifically, a teacher who receives a score of accomplished in the observation component and receives least effective growth would be rated as skilled ((600+0)/2 = 300). A second reason can be due to shared attribution where teachers receive often a higher rating than they themselves did not personally earn. Rather the shared student growth results of an entire district performance on the entire district report card, improved the teacher’s student growth measurement. A third reason was related to very subjective, teacher created student learning objectives that were often designed and controlled by the same individuals who they were intended to measure.

Figure 7: Numerical conversions for final summative ratings

Whether or not one agrees with the measures or calculations, the data indicates the evaluation system was not producing students who are better prepared for college and careers as was intended nor teachers who are better teachers. Accordingly, legislators have responded to the data analysis, public concern with the evaluation system, and consequently voted to implement a new, third OTES model for the 2020-2021 (SB 216). One state representative, Teresa Fedor, recently stated that the Ohio General Assembly had to make changes to the evaluation system as it “has been flawed and broken from the very beginning” (Siegel, 2018).

Better Classroom Instruction - Take 3

In rewriting the OTES for the third time, Ohio lawmakers indicated they need to construct a system that teachers and administrators think is fair, not overly burdensome and actually furthers the goal of better classroom instruction. Consequently, the newest revision to OTES requires “at least two measures of high-quality student data (HQSD) to provide evidence of student learning attributable to the teacher being evaluated” (ORC 3319.112). When applicable, the high-quality data will include the value-added progress dimension and one other measure of high-quality student data that demonstrates student learning. Student learning objectives may no longer serve as a student data measurement and districts are prohibited from using shared attribution. The revised model focuses on high-quality data that is specific to the teacher being evaluated.

Other expectations for the state board are to revise the specific standards and criteria that distinguishes between the different rating levels of the OTES rubric. A newly revised rubric has been constructed to align with the changes to the revised OTES model. Specifically, the new rubric now includes an evaluation of high-quality student data that can be used as evidence in any component of the evaluation, which are as follows:

A. Knowledge of students to whom the teacher provides instruction

B. The teacher’s use of differentiated instructional practices based on the needs or abilities of individual students

C. Assessment of student learning

D. The teacher’s use of assessment data

E. Professional responsibility and growth

(ORC 3319.112)

In addition to the inclusion of HQSD throughout the rubric, other areas of the rubric have completely changed. For example, in the 2019 draft of the OTES rubric, a new section on the entitled “classroom climate and cultural competency” has been added. Even though some areas have remained, they have been clarified or rewritten to emphasize important teaching skills. One example of this is in the new lesson delivery section. In the newest version, teachers are required to employ effective, purposeful questioning strategies to check for understanding, increase understanding, involve students in the lesson, and ask challenging questions about disciplinary content, engage students in self-assessment, and adjust the lesson based on student understanding. In the prior version, teachers were asked to have student-led lessons, anticipate confusion by presenting clarifying information before students asked questions, and develop high-level understanding through various types of questions.

More Support for Teachers

Many of the teacher performance criteria continue to be included in the newest revision of OTES such as the number (2) and length (30 minute minimum) of teacher observations and required classroom walk-throughs. A significant difference in the updated OTES framework requires that instead of two holistic observations, the revision now requires one formal holistic and one formal focused observation. The focused observation can relate to the goal(s) set in the professional growth plan and/or administrative suggestions/requirements. Ratings are expected to be assigned for each evaluation and the teacher should be provided a written report of the results of the evaluation. LEAs still have the option for teachers scoring an overall performance rating of skilled or accomplished to receive less frequent evaluation; skilled every two years and accomplished every three. Teachers will also continue to complete professional growth plans (and improvement plans when necessary) to guide their professional growth.

Another change relates to the goal setting for these professional growth plans. Previously, teachers could write goals that did not connect to performance. Under the revised process, teachers will now be required to align their professional goals to identified areas highlighted in the observations and evaluation. This will further support teacher and student learning as goal setting will be tied to the teaching-learning cycle and not be separate from the evaluation. Evidence of growth on the goal could even be demonstrated through the collection of HQSD data.

The Ohio Teacher Evaluation System is intended to support teacher development and improved student achievement. The model requires timely feedback and collaborative goal setting. LEAs are also expected to allocate financial resources to support professional growth. Plans to educate constituents throughout the state regarding the changes to the process and rubric are being developed.

Challenges to the Process

If our goal is to improve student and teacher achievement, how do we support teachers under this new model? As referred to in “The Opportunity Myth,” students need access to four key resources: grade appropriate assignments, strong instruction, deep engagement and teachers who hold high expectations. The challenge currently is that “Even though most students are meeting the demands of their assignments, they’re not prepared for college-level work because those assignments don’t often give them the chance to reach for that bar” (p. 21).

HQSD embedded in day-to-day instruction as the new model prescribes is one way to support this. Given the current draft,

The high-quality student data instrument used must have been rigorously reviewed by experts in the field of education, as locally determined, to meet the following criteria:

- Align to learning standards

- Measure what is intended to be measured

- Not offend or be driven by bias

- Be attributable to the specific teacher for course(s) and grade level(s) taught

- Demonstrate evidence of student learning (achievement and/or academic growth)

- Follow protocols for administration and scoring

- Provide trustworthy results

(ODE, 2019).

More training and support is needed to support LEAs in designing HQSD that fosters engagement and challenges students in the classroom. Without training and support, there could exist a wide variance of what schools believe to be HQSD and in how the new requirement is implemented. Without consistency, there could be the opposite effect on high teacher expectations and strong instruction.

Consequently, providing training and practice to LEAs is imperative to school improvement. An in-depth study examining the instructional practices in our nation’s classrooms revealed that, “Specifically of the 180 hours in each core subject area during the school year, students spend 133 hours that are not grade appropriate.” (TNTP, 2018). Teachers need to understand and utilize HQSD in their practice to support student learning.

Next Steps

Ohio piloting the revised OTES framework to all Ohio districts and community schools who elect to participate. Participating districts and schools who choose to conduct the pilot must fully implement all components of the system. Statewide implementation of OTES is planned for the 2020-2021 school year.

In order for this OTES model to be successful, schools will need supports. Specifically, training must be offered to help districts and schools recognize and implement HQSD. What makes an effective assessment and how to analyze the results are just some of the questions with which school districts will need support. Additionally, the revised rubric needs to be normed to ensure ratings are consistent across a school, district, and the larger state. Administrators are already asking for concrete examples of what various skills look like within their classrooms. And lastly, more focus will need to occur on the connection between the professional growth plan and the evaluation. As mentioned previously, a focused observation is now required. Ongoing training and support on how to provide strong feedback to teachers and formulate strong questions to evolve teacher self-reflection and practice will support both administrative and teacher development with the OTES revisions.

Ohio may be rounding its third revision of OTES, but there is an evolution to the process versus fresh slate. Revisions are based on student and teacher performance data, surveys and formal feedback from practitioners. As a state, educators continue to challenge themselves to improve instruction and provide more support to teachers and students in the learning process. OTES has been helpful in structuring a system for feedback and improvement in practice.

References

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. (2009). H.R. 1 — 111th Congress: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr1

Duncan, A. (2009). Robust Data Gives Us The Roadmap to Reform. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/news/speeches/2009/06/06082009.html

NCTQ (2011). OTES Training Workbook. Washington, D.C.: NCTQ.

NCTQ (2013). OTES Training Workbook. Retrieved from: https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/OTES_Training_Workbook_Updated

Ohio Department of Education (2017). Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. Retrieved from: http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Teaching/Educator-Evaluation-System

Ohio Department of Education (2019). High Quality Student Data. Retrieved from:

Ohio Department of Education (2019, February). Ohio OTES Prototype Day 2. Presentation presented at Regional Meeting for Ohio OTES Prototype Day 2 by the Ohio Department of Education, Medina.

Ohio Rev. Code §3319.112 (2018), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/3319.112

Ohio Senate Bill 216. S.B. 216 - 132nd General Assembly: Ohio Public School Deregulation Act.

Race to the Top. H.R. 1532 — 112th Congress: Race to the Top Act of 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr1532.

Seigel, J. (2018). Ohio teacher evaluations get an overhaul that teachers like. Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved from: https://www.dispatch.com/news/20180701/ohio-teacher-evaluations-get-overhaul-teachers-like

Strickland, Delisle, Cain (2010). Race to the Top Application: Ohio. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/phase1-applications/ohio.pdf

TNTP (2018). The Opportunity Myth. Retrieved from: https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf