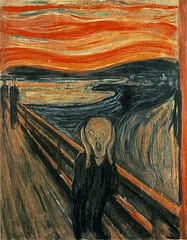

It may not be a coincidence that the most valuable modern painting is Edvard Munch’s The Scream and that new research suggests that the most effective merit-pay system is the threat of—Aaaaaah!!!—no pay.

What does The Scream have in common with merit pay? Photo by Ian Burt. |

Jay Greene takes on the issue in a wonderfully sassy post this morning headlined “In Chicago—Phony Merit Pay is Dead, Long Live True Merit Pay.” He recognizes that the ink isn’t dry on the deal hammered out between the Chicago Public Schools and the striking Chicago Teachers Union, but he suggests that it was a blessing (in disguise?) that CPS gave up on its attempt at “differentiated compensation” but retained the right to open new charter schools. As Greene argues, the former is “phony” merit pay and the latter is “true” merit pay:

In phony merit pay—the kind that hardly exists in any industry—there is a mechanistic calculation of performance that determines the size of a small bonus that is provided in addition to a base salary that is essentially guaranteed regardless of performance. You can stink and still keep your job and pay. The worst that can happen is you miss out on some or all of a modest bonus. To make it even more phony, in the few cases where this kind of phony merit pay has been tried, the game is often rigged so that virtually all employees are deemed meritorious and get at least some of the bonus.

Greene says that the most effective merit pay system is the one that gets you the best teachers. As he writes,

The net effect of growing charter schools, closing under-enrolled traditional public schools, and only hiring back the best and most desired teachers from those schools is a true merit pay system. Bad teachers are let go. Good teachers not only get their job back, but they also get an extremely generous pay raise over the next four years for staying and being good. That’s real merit pay.

At a more micro level, recent research by Freakonomics co-author and University of Chicago professor Steven Levitt, Harvard professor and MacArthur "Genius Grant" winner Roland Fryer, Chicago's John List, and University of California San Diego's Sally Sadoff, supports this seemingly harsh view of performance-boosting incentives (for a quick introduction, read Amber Winker’s analysis). National Public Radio’s Shankar Vedantam took up the question this morning, interviewing John List about the group’s “loss aversion” study of 150 K-8 teachers in the Chicago Heights school district, a hard-scrabble community twenty miles south of Chicago proper where almost all the students are poor and only 64 percent meet minimum proficiency standards. The researchers divided the teachers into three groups, as Vedantam says,

One group got no incentive; they just went about their school year as usual. A second group was promised a bonus if their students did well at math.

The third group is where the psychology came in: The teachers were given a bonus of $4,000 upfront — but it had a catch. If student math performance didn't improve, teachers had to sign a contract promising to return some or all of the money.

The third group burned up the competition. "Teachers who were paid in advance and [were] asked to give the money back if their students did not perform,” List tells NPR, “—their [students'] test scores were actually out of the roof: two to three times higher than the gains of the teachers in the traditional bonus group." List said he believed that the loss aversion incentive was so successful because it made teachers focus on the kids who were not mastering the material and stick with them until they got it.

Writing about the study last July, The Atlantic’s Jordan Weissmann called it a “major breakthrough.”

There are, of course, the caveats; the data on reading scores, for instance, said Weissmann, were “shakier, since most students ultimately had more than one instructor working with them on language skills.”

And then there’s the politics of the thing. As Vedantam notes, “List warned that the bonus system needed buy-in from teachers. Teaching isn't like making widgets; it requires motivation and passion. If teachers feel they are being manipulated rather than encouraged to improve their performance, they could end up looking for other lines of work.” Or they might just choke under the pressure. “From the perspective of a teacher's union,” says Weissmann, “it's easy to see how this would make the [merit pay] concept even more unpalatable—who wants to subject themselves to the stress of seeing their bonus stripped away?”

This is where we come back to Jay Greene. A brand-new system (“non-unionized,” in Greene’s view) offers the advantage of starting fresh. Knowing the rules going in—e.g., that you will be judged on performance (yours and your students) and that you could lose your job—makes it much easier to establish a collaborative and school-based incentive system. As Kathleen Porter-Magee suggests, “Top-down systems that bypass or undermine school leaders rarely produce excellence in the classroom.” In this case, the “top-down” applies just as well to federal and state bureaucrats as it does to organized labor.

So, though the ink isn’t dry yet, Chicagoans may have dodged a bullet without knowing it. The new CTU contract will not have the “phony” merit pay (differentiated pay) but will have the “real” thing (school autonomy). Whether it becomes an Edvard Munch moment is anyone’s guess. But it should be better for students.