For years, career-technical education (CTE) was saddled with a bad reputation. The stigma was not undeserved, as it was all too often a “dumping ground”—as a Rand Corporation study once put it—for students whom schools believed could not succeed academically. Regrettably, low-income, special-education, and minority students were more likely to be placed in these weak “vo-tech” programs, leaving them with menial skills and little hope for career advancement after high school.

Understanding the harms of this approach, policymakers have worked in recent years to upgrade CTE. One way that Ohio has sought to strengthen career-tech is by encouraging students to attain industry-recognized credentials (IRCs). Earning these IRCs is supposed to bolster students’ technical skills and signal their readiness for jobs in the real world. Today, Ohio students can pursue a wide range of IRCs that include welding or plumbing certificates to professional certifications such as a state-tested nursing assistant.

But these IRCs are only good for students if they have value in the workplace. Otherwise, they’re not worth the paper they’re printed on, and worse yet, they take time and attention away from pursuing academic competencies and technical skills that will better serve students when they head to work.

On the positive side, Ohio incentivizes high-value IRCs through the Innovative Workforce Incentive Program (IWIP). This program provides schools up to $1,250 when students earn IRCs in selective career fields such as healthcare and manufacturing.

On the other hand, the state does a poorer job encouraging high-quality IRCs through its graduation requirements. As discussed in this piece, a lack of quality control appears to have allowed schools to push struggling students to the finish line through low-level IRC “pathways.” If not corrected, this will be another troubling example of low-quality CTE programs being used to shortchange students.

***

As a quick refresher on Ohio’s graduation requirements, students struggling to meet state “competency” standards—i.e., passing the Algebra I and English II exams—have a variety of alternative routes to graduation, including earning IRCs. To implement this option, the state has utilized a system in which each IRC on a wide-ranging list of roughly 600 credentials is assigned a value between one and twelve points. Students can meet the competency element for graduation if they earn at least twelve points in a particular career field.[1]

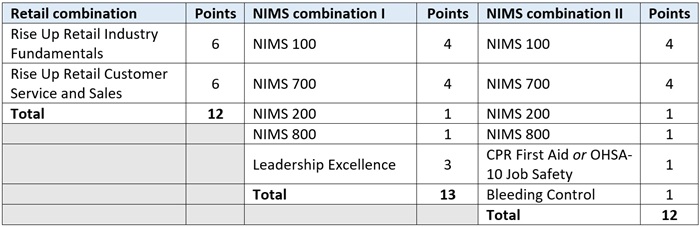

The points system correctly recognizes that not all IRCs are of equal value. But the state also allows students to “bundle” multiple IRCs to meet the twelve-point mark. A student doesn’t need to earn a single high-value, twelve-point credential to graduate. Instead, they can accumulate a bunch of IRCs (within a career field) that add up to twelve points.

Table 1 provides examples of how this “bundling” works, using illustrations that will be relevant when we turn to actual IRC data. We see, for instance, that a student can meet graduation requirements by collecting two retail-based certificates. While retail occupations deserve our respect, it’s also an industry that pays relatively low wages, particularly for workers with weak math and reading skills who are unlikely to move into the management ranks. It’s also somewhat odd to see these certifications offered as a graduation pathway, as most retailing jobs don’t require these credentials.

The other two columns display IRC combinations based on emergency management certificates known as NIMS. Though they may sound impressive, the courses range from just two to four hours long and students could presumably rack up these certificates in a few weeks. They couldn’t rely solely on the four NIMS credentials to graduate, as they only add up to ten points. But that’s where bundling comes into play—to reach twelve points, just one or two additional IRCs are needed. One option is to complete a “leadership excellence” certificate—of which we know just about nothing—worth three points. Another is to complete two of three of the following one-point credentials: CPR First Aid, OSHA-10 hour job safety, or bleeding control certificate. These IRCs are more akin to supplements that provide some useful skills and workplace knowledge, but are not designed to be “core” technical credentials that by themselves help young people get hired or advance in the workplace. Overall, it’s extremely hard to tell how students benefit from these NIMS bundles.

Table 1: IRC combinations that equal twelve or more graduation points

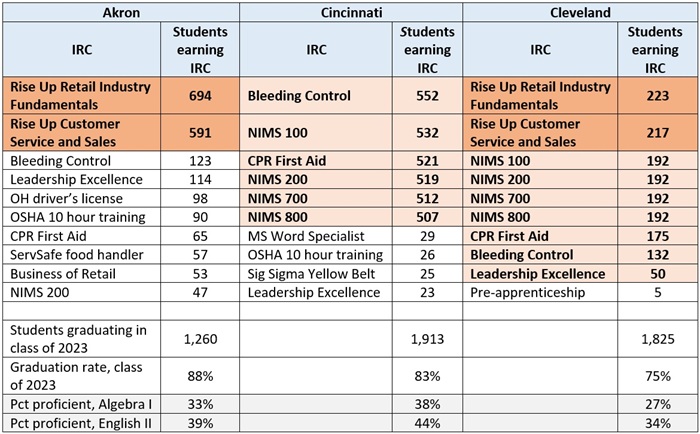

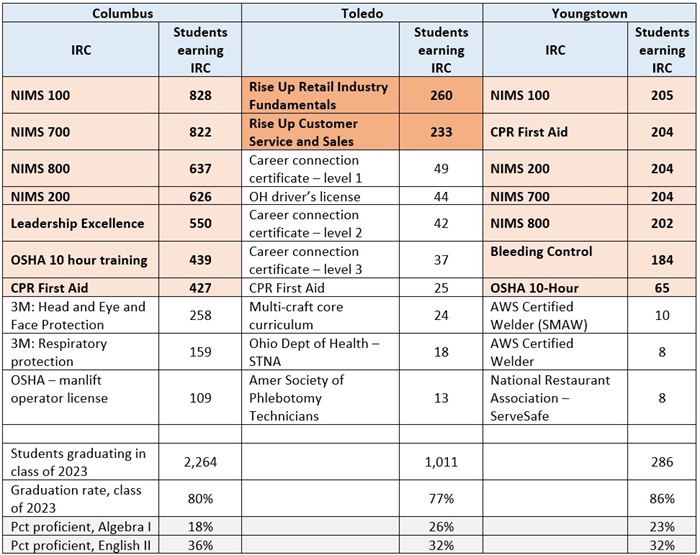

As we at Fordham have discussed previously, and show again here, Ohio’s urban school districts are using these dubious IRC-based alternative “pathways” to graduation. Consider the data below, which shows the most commonly earned IRCs in Akron, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Toledo, and Youngstown. It’s striking to see only a few IRCs—out of the hundreds that students can earn—dominating the top of these lists. These include the two retail-based certificates and the NIMS certifications, along with the CPR First Aid, bleeding control, and OHSA job-safety certifications. The retail combination—shaded in darker orange—seems to be a widely-used route to graduation in Akron, Cleveland, and Toledo. Meanwhile, the NIMS bundle appears to be commonly used in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Youngstown. The tables also note the districts’ low proficiency rates in Algebra I and English II, which suggests that they were likely searching for alternative routes to graduation for off-track students.[2]

Table 2: Ten most commonly earned IRCs in urban Ohio districts, class of 2023

* * *

Serious career-and-technical education puts students on a pathway to rewarding careers after high school. To truly be a “pathway,” it should be a structured program that includes career exploration during middle school, rigorous technical coursework in students’ career field of choice, pursuit of a credential (if applicable to the profession), and work-based learning.

Unfortunately, what’s appears to be happening in Ohio’s urban districts is some kind of distorted form of CTE in which low-achieving students are getting routed into less rigorous IRC programs to get them diplomas at the last minute. This does nothing for the students who receive certificates that have nothing to do with their career aspirations and have little value in the workforce. Worse yet, subjecting struggling students to this workaround robs them of opportunities to gain real technical skills and achieve academic proficiency.

Ohio policymakers need to put a stop to this, and there are ways to do it. They could, for instance, add a stipulation that a student must earn a nine- or twelve-point IRC to meet the alternative graduation pathway. Policymakers should also remove lower-tier “supplemental” credentials (e.g., CPR First Aid or bleeding control) from the state-approved IRC list. These are nice-to-have certifications—and nothing would stop students from attaining them voluntarily—but the state would choose to not “nudge” students into collecting them for purposes of graduation. Removing these certificates would follow ExcelinEd’s recommendation that these types of “general readiness” credentials “not be considered industry-recognized credentials in the way that they currently are in state CTE programs.”

However it gets done, Ohio cannot allow CTE to become the “dumping ground” for low-achieving students again. That approach wrote off kids who were struggling and left them without a fighting chance to succeed after high school. Let’s not let the past repeat itself.

[1] Students can also earn one of the two required “readiness seals” needed to graduate by earning twelve IRC points.

[2] The state requires students to achieve test scores slightly below proficient. The proficiency data (from 2023-24) do not directly reflect the proficiency rates of the class of 2023; however, these districts have long posted low proficiency rates.