Are parents and taxpayers being misled? The proficiency illusion strikes again

Revealing the "honesty gap"

Revealing the "honesty gap"

Are states dutifully reporting the fraction of students who are on track for college or career? According to a new report from Achieve, a nonprofit organization that assists states in education reform efforts, the answer is no—and Ohio has been one of the worst offenders.

The report documents the discrepancies between proficiency rates on state tests versus the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP). Achieve’s analysis finds that most states “continue to mislead the public on whether students are proficient” by reporting proficiency rates on state assessments that are significantly higher than those on NAEP. This is a serious problem since NAEP—commonly referred to as the Nation’s Report Card—has long been considered the gold standard of measuring student achievement and, more recently, college preparedness. As Fordham’s Mike Petrilli and Chester Finn explained a few weeks ago, there’s now good evidence that NAEP’s proficiency level in reading is particularly predictive of whether students are ready to succeed in college without taking remedial courses.

Ohio’s longstanding definition of proficiency, on the other hand, is predictive of nothing, as far as we can tell. It certainly doesn’t indicate that a student is on track for college. But that’s surely what parents believe when they receive a test score report saying that their children passed at the proficient level.

It’s also worth noting that this isn’t the first time questions have been raised about whether states are misleading parents and the public about student proficiency—back in 2007, Fordham took the questions head-on in our study The Proficiency Illusion.

Achieve’s report notes over half of states’ discrepancies in state versus 2013 NAEP results are more than thirty percentage points. Ohio is one such state. In 2013–14, Ohio’s state tests scores differed by at least thirty percentage points or more in each of NAEP’s main test subjects: fourth-grade reading and math, and eighth grade reading and math. In fact, in fourth-grade reading, the difference between NAEP and Ohio test scores is a whopping forty-nine points. Such large score discrepancies support Achieve’s troubling analysis that many states—including Ohio—are classifying too many students as proficient when they actually aren’t anywhere close to being on track for entering college without remediation.

Fortunately, several states are working hard to decrease what Achieve has dubbed the “honesty gap.” The states that have decreased discrepancies between NAEP and their state test scores appear to have three strategies in common: raising academic content standards, utilizing higher-quality tests, and raising the cut score for proficiency.

For example, many of the states that have raised student achievement while simultaneously lowering NAEP/state test discrepancies are early adopters of Common Core and Common Core-aligned assessments. Kentucky is a prime example. As the first state to adopt Common Core back in 2010, Kentucky has been faithfully implementing the standards ever since. The Bluegrass State’s energetic implementation efforts have led to a significant rise in student achievement, but they’ve also led to smaller discrepancies between state tests and NAEP. In each of the previously mentioned test subjects, Kentucky’s discrepancies are half that of Ohio’s. In fourth-grade math, the discrepancy is as little as eight percentage points, and in eighth-grade reading, Kentucky is one of the five states with the smallest discrepancies (along with Wisconsin, New York, Utah, and Tennessee). Kentucky also offers a good example of transitioning to a more difficult test. After initially signing on to PARCC and Smarter Balanced, Kentucky left both consortia and instead chose to develop its own Common Core-aligned test. These new tests were harder, and Kentucky initially saw a drop in proficiency rates. But those rates are now improving (along with a slew of other measures), and as a result, the state is seeing a rise in proficiency that truly reflects student learning.

New York offers a similar example. While Common Core implementation and a move to higher-quality tests has been more controversial in New York than in Kentucky, the Empire State has benefited from both. Since 2010, when New York first adopted Common Core and its aligned assessments, the difference between its state test scores and NAEP scores has narrowed significantly. But narrowing the honesty gap in New York isn’t merely the result of high standards and rigorous tests. In fact, it’s largely due to raising cut scores. Back in 2010, New York experienced firsthand just how hard it is to tell the truth; cut scores were raised, the number of students who were deemed proficient dropped, and parents and the public were outraged. But after the initial frustration over lower proficiency scores, New York settled in and got to work—and it paid off. In each of the four aforementioned test subjects, New York has one of the lowest discrepancies between state tests scores and NAEP. In fact, New York even has a positive difference in fourth-grade reading and eighth-grade reading and math; in other words, New York has proficiency requirements that are more rigorous than NAEP.

Telling the truth can be scary, particularly when the truth is predated by a history of reporting inflated proficiency rates. For policymakers, it can be tempting to keep cut scores, standards, and test quality low in order to avoid the hard truth that too many students aren’t on track for college or a well-paying career. But students, families, and the public deserve to know the truth about student achievement, even if it’s not pretty. Only after confronting the truth can we move on in the right direction. States with large discrepancies between state test scores and NAEP should beware of how uncomfortable the future will be if they continue to indulge in the false comfort of the honesty gap. Thankfully, Ohio is finally on the brink of closing the honesty gap: PARCC is a more difficult test, and its proficiency cut scores are expected to be quite demanding. Governor Kasich and other Buckeye policymakers should be commended for maintaining their support during a difficult transition—and for their commitment to telling the truth to Ohio students and families.

Since its birth in 1997, Ohio’s charter school program has been on a bumpy ride. Overall sector quality has been mixed, and Ohio charters have been bogged down by controversy, some of it based on partisan politics. But a new day is dawning for the Buckeye State’s charter schools. State policymakers have begun to embrace charter governance reforms. Governor Kasich and the legislature—with support from both parties—have worked together to craft legislative proposals that, if enacted, would remedy Ohio’s broken charter school law and create new incentives aimed at expanding high-quality charters throughout the state. Presently, the Ohio Senate is considering the charter reform bills.

We at Fordham have voiced our loud and clear support for charter reform in Ohio. But we’re not the only voices seeking big changes. In addition to support from key policymakers, editorial boards, and business organizations, the leaders at some of the Buckeye State’s very finest charter schools have also taken a stand and are demanding change as well. At committee hearings in the Senate on May 6 and the House on March 11, legislators heard from three leaders of Ohio’s high-quality urban charters. Here are some highlights of their testimony:

Superintendent Judy Hennessy of Dayton Early College Academy, a high-performing charter that serves more than 80 percent low-income and minority students, told the members of a Senate committee that “greater transparency in the operations and governance of charter schools will help remedy some of the flaws in existing legislation.” Specifically, she emphasized the need for greater financial transparency, a simpler school consolidation procedure, and greater access to facility funding (especially scarce for Ohio charters).

Andy Boy, founder and CEO of the United Schools Network in Columbus, zeroed in on the proposals for strengthening sponsorship (a.k.a. “authorizing”). He told lawmakers, “When we launched our first school, we spent considerable time researching sponsors. In some cases we were appalled by the easy application process and lax attitude around the real challenges of a startup school.” The benefit of the proposed charter reforms, he said, is that it “empowers the Ohio Department of Education to approve, evaluate, and publicly rate all charter school sponsors, including previously grandfathered sponsors.…By holding sponsors more accountable, we will improve the charter school landscape in Ohio.”

John Zitzner, president of the Friends of Breakthrough Schools in Cleveland, spoke before a House committee in support of the charter reforms contained in the governor’s proposals. More specifically, he commended the proposed $25 million facility fund that would be made available to schools sponsored by exemplary charter sponsors, calling the fund “much needed.” Yet he also expressed concerns about whether the fund should be accessible to high-performing individual schools, regardless of the rating of their authorizers. How state lawmakers determine access to the proposed state facility fund is one question worth watching in the waning days of this legislative session.

Buckeye lawmakers have a great opportunity to vastly improve Ohio’s charter schools by laying the policy groundwork needed for the sector to thrive. They should take stock of the testimony of those who lead our highest-performing charter schools—the leaders who are forging a stronger charter school sector for Ohio.

When the Foundation for Excellence in Education released its first “Digital Learning Report Card” in 2011, the state-by-state outlook for ed-tech innovation was worrying. Twenty-one states received failing grades. Four years on, the picture looks very different. While there are still only two states—Florida and Utah—earning A grades, this year’s scorecard shows half of them with improved grades and just five (Connecticut, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, Tennessee) with Fs. Barriers to digital learning are falling fast.

The report card grades states on ten “elements of high-quality digital learning,” including whether students can advance by demonstrating proficiency (not merely by warming classroom seats for enough months) and whether they have the ability to customize their education through digital providers. And of course, the funding and infrastructure must be in place to support digital learning. Broadly speaking, the report praises states for adopting policies that embrace new models and ways of thinking, and shames them if they don’t. States might get dinged, for example, if they restrict student eligibility for online courses (allowing kids only to take online versions of courses already offered in schools seems truly pointless). That said, some of the report’s criteria feel more like an ed-tech enthusiast’s wish list than a coherent framework to encourage “student-centered” learning. It makes sense, for example, to reward a state for ensuring that all students “have access to high-quality digital content and online courses.” But is it really important that “all students must complete at least one online course to earn a high school diploma”? Similarly, it’s not entirely clear why students’ ability to “customize their education using digital content through an approved provider” is important to anyone other than said providers. What matters more to students: customized learning or customized digital learning?

The sudden surge in access to digital learning (and rapid dismantling of barriers) chronicled by this year’s report card is occurring despite a steep drop in legislative activity in the last year; the report notes that only fifty new digital learning laws were passed by states last year. But like a python swallowing a pig, states were busily digesting more than four hundred such measures enacted since 2011. Perhaps the area of greatest movement has been in competency-based education. Connecticut finished dead last in its overall grade, but the report holds up as a model its recent measure to allow students to earn credits by meeting non-traditional, mastery-based standards. The Digital Learning Report Card is a welcome source of encouragement for educational innovation, though it obviously tends to privilege blended learning over other forms of instruction. This edition leaves the unmistakable impression that the future of education is arriving faster than we think.

SOURCE: Digital Learning Now, “Digital Learning Report Card 2014,” Foundation for Excellence in Education (May 2015).

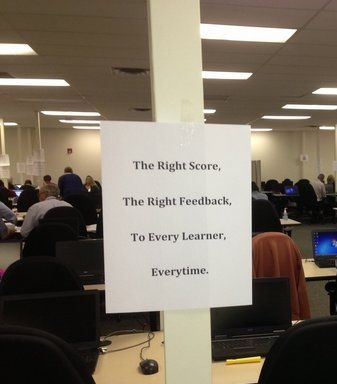

Plain Dealer reporter Patrick O’Donnell was given access to a Pearson test-grading facility in suburban central Ohio recently and filed a series of reports from inside its walls. The tone of the pieces is reminiscent of that M*A*S*H episode when the newsreel reporter interviews the frontline medical staff. It is painstaking work in a high-pressure environment, but it is important and must be done with diligence and a touch of humor. Like the sign in the office says:

First up, O’Donnell runs us through the basics of the operation. Most graders tackle one question only, scoring the same one for hundreds of students in a shift; “anchor” examples show the basic form the correct answer should take; and there is selective double-checking of live scorers’ work.

Then there is a look at who has been hired to do the scoring work for Pearson this year. Some 72 percent of all their test graders nationwide have some teaching experience. And yes, some of them were hired via Craigslist.

Finally, while O’Donnell has a reputation as a thorough reporter on his own, he decides to open up the floor to Plain Dealer readers to find out what questions they had about how the grading of PARCC tests works in practice. After some softballs about rest breaks and training levels, we arrive at the coup de grâce—the killer question that the inquirer was likely certain would break the back of the testing conglomerate and end the standardized testing madness in Ohio forever: “Do you think students are being scored fairly? Would you want your child to be scored this way?" You’ll have to read the story to find the answer.

Much attention has been paid to why teachers quit. Statistics and studies get thrown around, and there are countless theories to explain the attrition rate. While recent reports indicate that the trend might not be as bad as we’ve thought, teacher attrition isn’t just about whole-population numbers—it’s about retaining the most effective teachers within those numbers. Indeed, a 2012 study from TNTP (formerly known as the New Teacher Project) notes that our failure to improve teacher retention is largely a matter of failing to retain the right teachers. A separate study suggests that retaining the best teachers is all about reducing barriers that make teachers feel powerless and isolated. The 2014 National Teacher of the Year recently pointed out that, among myriad other causes, lacking influence in their own schools and districts (let alone in state policy) is often at the root of teacher attrition.

Keeping high-performers in the classroom has long been a trouble spot for schools. “If you don’t offer leadership opportunities for teachers to excel in their profession, to grow, and still allow them to stay in the classroom,” says Ruthanne Buck, senior advisor to Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, “you are asking for your best and brightest teachers to leave.” For teachers who want to make a bigger impact, take on new challenges, or be paid more for sharing their expertise, options are largely limited to administration. In fact, schools often push high performers into managerial roles simply because there’s nowhere else for them to go. Districts that do offer teacher leadership roles often frustrate good teachers rather than maximizing their potential. Ross Brenneman described this problem well: “In their haste to promote the concept of teacher leadership, [districts and schools] fail to offer any kind of meaningful leadership roles, equate added tasks to leadership, or merely try to put teachers on an administrative track.” In other words, even if schools aren’t encouraging their best teachers out of the classrooms where they’re sorely needed, they’re probably burning them out by piling on more responsibilities without added support.

In an attempt to solve this problem, Duncan created Teach to Lead, a program that promotes teacher leadership ideas and their implementation. The program seems to be having some success nationally. Public Impact is also facilitating successful innovations through their Opportunity Culture initiative. But what about locally driven approaches? Is there something Ohio schools can do to ensure that their best teachers are more likely to stay in the classroom? The answer is yes, and one way to accomplish this is for schools to embrace the power of “hybrid” teachers.

A hybrid role is one in which the best and brightest teachers instruct students and hold additional leadership responsibilities. Paul Barnwell, a public school teacher in Kentucky, recently wrote a piece about the benefits of leveraging teachers into hybrid roles. For Barnwell, it takes the form of becoming what he dubs a “teacherpreneur.” He teaches morning classes at a Louisville high school, then spends the afternoons “designing and implementing opportunities for professional learning in virtual spaces.” Barnwell therefore impacts kids in the classroom and also furthers his influence by designing professional development for teachers. Professional development efforts are notoriously bad, and the prospect of having a highly effective, still-in-the-classroom teacher help reshape them should make both teachers and administrators drool in anticipation.

But the promise of having productive professional development is only one of the potential benefits of hybrid teachers, who can be deployed in all sorts of ways. Districts could train them to conduct evaluations and lessen the administrative burden on principals; as mentors, they could devote consistent, meaningful time to observing and coaching a cohort of first-year teachers; state boards of education and legislators could consult them on potential policy changes and improvements; groups of teachers from different districts but similar content areas could meet, exchange best practices, and report back to their home districts. NPR recently examined hybrid teachers who are multi-classroom instructors, hired by a school or district to teach classes and oversee a group of colleagues. While the possibilities for hybrid teachers are endless and unique, they all orbit around one central idea: High-performing teachers should be in leadership roles without leaving the classroom and should be provided with additional resources (such as time) to fulfill those roles. If schools give great teachers an opportunity to expand their influence and grow professionally, great teachers will stay—and students and colleagues will benefit.

Making room for more hybrid teaching roles is a promising solution that could be piloted, refined, and scaled up. Hybrid roles offer an equal exchange—teachers are given more responsibilities to create a bigger impact, but the added burden is alleviated by giving them time outside of class to lead. It might mean hiring more teachers, but if the trade-off is retaining highly effective teachers and maximizing their impact, then student achievement should trump the incremental cost.

In 2006, Ohio enacted one of the nation’s first “default closure” laws, which requires the lowest-performing charter schools to shut down whether their authorizers want them to or not. The law, still in effect today, has forced twenty-four charters to close. The criteria for automatic closure are well defined in law and are based on the state’s accountability system.

This new working paper, which complements our recent study on Ohio school closures, evaluates the effect of closures induced by the automatic closure law on student achievement. (By contrast, Fordham’s study examined both district and charter closures that occurred regardless of cause, be it financial, academic, or other.) To carry out this analysis, the researchers compared the outcomes of students attending charters that closed by default to those of pupils attending charters that just narrowly escaped the state’s chopping block. The sharp “cut point” for closure versus non-closure allowed the analysts to compare very similar students who attended similarly performing schools—thus approximating a “gold-standard” random experiment.

The key finding: Students displaced by an automatic closure made significant gains in math and reading after their schools closed, a result consistent with our broader study. Moreover, the analysts found that the academic benefit for students affected by automatic closure was actually greater than the benefit for students displaced by other types of closure. The analysts estimate a 0.2 standard deviation increase in achievement after automatic closure—nearly double the effect size found in our broader closure analysis. (For some context, the black/white achievement gap is about one standard deviation.)

This suggests that Ohio’s automatic closure law has worked as intended; it forcibly shut down some of the worst-performing schools in the state, to the benefit of the children who had attended them. Meanwhile, other states could follow the example of Ohio—and ten other states—by passing an automatic closure law. Perhaps a bigger question is whether Ohio should create a default closure for poorly performing district schools, too. After all, it’s a state’s obligation to ensure that no child, regardless of her socioeconomic circumstance, ends up in a rotten school.

SOURCE: Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu, “The Effect of School Closure on Student Achievement: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Ohio’s Automatic Charter School Closure Law,” Working Paper (March 2015).