Schools were made to help students, not the other way around

It’s frustrating feeling like a broken record, but Stephen Dyer’s comparisons between school districts and charter schools can’t go uncontested.

It’s frustrating feeling like a broken record, but Stephen Dyer’s comparisons between school districts and charter schools can’t go uncontested.

It’s frustrating feeling like a broken record, but Stephen Dyer’s comparisons between school districts and charter schools can’t go uncontested. His analyses are reductive, crudely simplifying poor families’ quest for better schools as mere financial transactions that—he claims—unduly harm school districts. Yet he ignores the harm that’s caused when a student attends an unsafe or educationally unsound district school. He overlooks the harm when somebody else’s child is cheated out of beautiful, high-quality learning experiences--the kind that we seek for our own children.

Given Dyer’s long established ties to active charter opponents—Innovation Ohio, the teachers unions, and the Know Your Charter project—it’s not surprising that he routinely places the interests of districts and the adults they employ ahead of families and children simply seeking a quality educational environment that meets their needs. Each blog he writes lays bare the common yet wholly fallacious view that state education dollars are “owned” by districts. Districts receive state funds to ensure that students can receive a publicly funded education in a publicly accountable institution; when a student leaves, so should those dollars.

This edition of “I can’t even, Stephen” has to do with yet another of his common practices: putting the “performance index” scores of giant school districts serving tens of thousands of children up against the scores of individual charter schools. He asserts that this comparison is justified because the performance index (a weighted measure of student proficiency on state exams) dictates charter start-up eligibility: Districts that fall into the bottom five percent on this measure are designated “challenged,” which means they’re places where new charters can locate.

A refresher on why this comparison is misleading: If you contrast Columbus City district, which includes schools in highly educated, wealthy neighborhoods, with schools located in the city’s toughest neighborhoods, the district will come out ahead. That’s generally true whether those schools are district-run or charter. Years of social science research has found that school performance on proficiency-based metrics largely correlates with income.

But let’s talk about the second part of this and how alarming it is. When districts earn scores low enough to trigger eligibility for charters to locate there, charter opponents view this as a sanction for districts. In other words, they view poor families’ ability to access better alternatives for their kids as punishment for districts rather than opportunities for people.

Imagine treating other family-driven choices—especially when the choosers are mostly black, brown, and poor—as a sanction on the institution from which those families fled.

Now imagine that those leading the complaints most likely have never been trapped in a schooling situation they couldn’t buy or move their way out of.

Okay, now try these on for size:

It’s obvious how self-centered and selfish these statements are and how ridiculous they sound. They place institutional interests above the needs of clients or patients each time. Yet such arguments are made repeatedly in education and largely go unchallenged.

If a family isn’t forced to select the hospital, daycare center, trauma treatment center (or library, grocery, bus stop, etc.) closest to their house, why on earth do we force families to do that with schooling? To suggest that families should have no choices because their neighborhood institutions lose money—be they hospitals, daycares, or schools—is outlandish. In almost no other instance do we give primacy to the effects of private choices on public institutions. We don’t force people to stay in deteriorating urban cities—or even struggling rural areas—simply to ensure that public services are maintained. Rather, we expect these places to reinvent themselves to attract and retain residents and/or “right-size” their budgets in ways that match present realities. The same should apply to school districts.

Nevertheless, people like Dyer continue to say these things out in the open, in plain daylight, even with pride, about schooling. They fight to enact policies to keep people in their “zones” to ensure that institutional—rather than family and student—needs are met. In this type of system, the primary losers are nearly always the poorest among us. Does this make you angry yet?

Most American teenagers plan to head off to college after high school. In my organization’s recent survey of over 2,000 U.S. adolescents, a strong majority reported plans to attend a four-year university (62 percent), while another quarter said they’ll attend a two-year college or trade school. According to survey data from Learning Heroes, 75 percent of parents expect their own child to earn a college degree. Almost 70 percent of high school graduates do in fact matriculate directly to college.

Kids’ and parents’ aspirations are admirable, as data show that adults holding bachelor’s degrees tend to fare better. A four-year degree is associated with higher lifetime earnings, lower unemployment rates, higher rates of homeownership, and more lasting marriages. While there are many “good jobs” available to people without a bachelor’s degree, it’s still a good bet to earn such a credential.

But how many of Ohio’s young adults have actually made it “to and through” college?

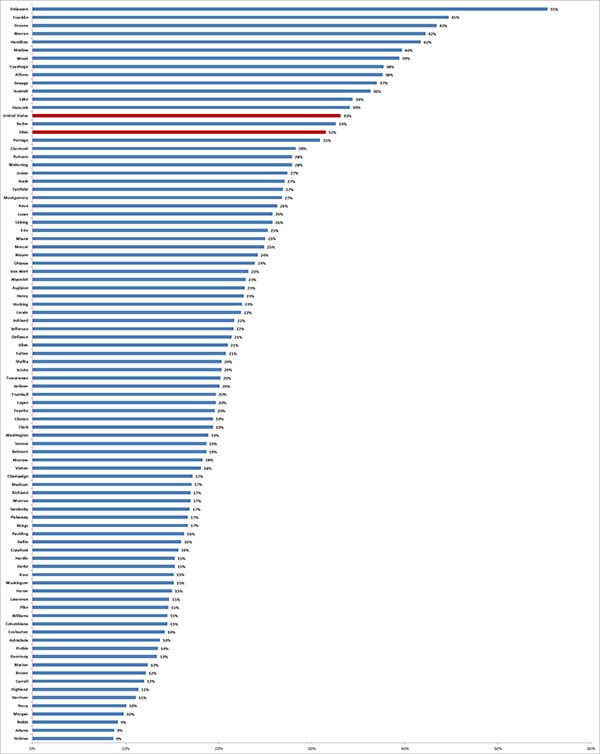

Data from the 2011-15 American Community Survey indicate that 32 percent of Ohio’s 25 to 34 year olds—“millennials” roughly speaking—hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. This proportion falls just below the national average of 33 percent; in relation to other large Midwestern states, Ohio lags behind Illinois (39 percent) and Pennsylvania (37 percent) and is more on par with Wisconsin (33 percent) and Michigan (31 percent) in terms of college attainment. These data include both “home grown” college grads as well as young people from outside of the state who migrate there.

Chart: Percent of 25–34 year olds with a bachelor's degree or higher, Ohio counties

Note: These are estimates with a margin of error typically in the range of +/- 2 to 5.

(Click to view the chart at a larger resolution.)

Even more striking, however, is the variation in college-educated millennials by Ohio county. As the chart here indicates, several counties in Ohio have relatively large populations of college-educated young people: The rates top 40 percent in Delaware, Franklin, Greene, Warren, Hamilton, and Medina counties. Not surprisingly, these are major metropolitan areas where the employment opportunities are likely the greatest. (Columbus is in or near Delaware and Franklin counties; Cincinnati is in or near Greene, Warren, and Hamilton; and Cleveland is near Medina.) At the lower end of the spectrum is a large number of Ohio counties—mainly representing small town and rural areas—where fewer than one in four young adults hold bachelor’s degrees, attainment rates that are below the national and state averages. To be certain, this excludes those who have earned an associate’s degree,[1] but the overall picture of college attainment among young adults is still grim across broad swaths of Ohio.

What to make of these data?

First, it’s striking to note the disparity between college aspirations and actual degree attainment. While the recent survey data cited in the introduction reflect the hopes of current students, surveys of high school seniors going back to 2000—thirty-five-year-olds today—also find strong majorities (about 70 percent) saying they expect to complete college.

Second, the regional variation across Ohio in its college-educated workforce could have implications for economic growth. Again, many good careers don’t require a bachelor’s degree—and perhaps a greater share of job opportunities in more rural locales can be met with something less than a four-year degree (but probably require more than a high-school education). By the same token, the fact that in some regions of Ohio, vast majorities of young adults don’t hold a college degree remains troubling. As data from the Greater Ohio Policy Center indicate, many small towns already suffer from high unemployment rates and population loss. While the labor markets and culture of these regions differ from metropolitan areas, the data raise questions around whether these communities can compete economically without a substantial, college-educated workforce.

Third, it would be helpful to better understand why college attainment rates are so low across parts of Ohio. Certainly much of it is explained by economics—jobs for college-educated people aren’t as plentiful, and they simply migrate to places where the opportunities are. But how much of the low rates reflect other factors? A recent article from the Hechinger Report suggests that some rural students feel discouraged from pursuing college, potentially explaining the lower matriculation rates among lower-income rural students. Those who do enroll might face greater roadblocks to completion such as the costs of higher education or inadequate academic preparation; this may in turn lead to lower rates of college persistence among students from poorer rural areas.

The news on the college-attainment front isn’t all bleak for Ohio. Statewide, there has been an uptick in bachelor’s degree attainment, which stood at 29 percent among 25-34 year olds in the 2005-09 ACS data; most counties also saw modest increases in this same timeframe. Nevertheless, the low attainment rates in various parts of Ohio raise interesting questions, as does the divergence between high school students’ college aspirations and reality. In the end, Ohioans should ask what it would take to ensure that a next generation of young people has the ability to make it all the way through a post-secondary education program—whether collegiate or vocational—that can set them up for a lifetime of success.

[1] Associate’s degree data are not available by age group; about 8 percent of all adults (25 and older) in Ohio hold an associate’s degree as their highest level of education.

To give some added oomph to excellent teacher preparation, the Council of Chief State School Officers launched the Network for Transforming Educator Preparation (NTEP) in 2013. Its purpose is to identify states with track records of innovative teacher preparation and support them in their efforts to implement aggressive and lasting improvements. The network’s first cohort included seven states: Connecticut, Idaho, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Washington. In 2015, they were joined by eight more states: California, Delaware, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah.

A new report examines the progress of those states, mainly in four key areas: stakeholder engagement; licensure reform; preparation program standards, evaluation, and approval; and the use of data to measure success.

In the realm of stakeholder engagement, participating states were required to outline how they would gain the “public and political will to support policy change.” Collaborations between stakeholder groups led several states to recognize the importance of clinical practice for new teachers. For instance, a working group made up of the Louisiana Department of Education, that state’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, and the Board of Regents collaborated to create a yearlong classroom residency for new teachers alongside an experienced mentor teacher that is complemented by a competency-based curriculum.

Since states determine their own teacher licensure policies, NTEP focuses on how participating states could ensure that candidates who earn licensure are ready for the rigors of the classroom on their very first day. States have made strides in various ways, including requiring performance-based licensure assessments, setting higher minimum GPA requirements for entry into preparation programs, and requiring programs to extend and improve candidates’ clinical experiences. But difficult challenges remain, including license reciprocity across state lines and establishing effective multi-tiered licensure systems.

Another important reform that NTEP states are pursuing is toughening their approval and reauthorization standards for teacher preparation programs. States like Kentucky made progress in this domain by developing an accountability system that includes information about the selectivity of programs, the performance of candidates on licensure exams, and scores on evaluations of practicing teachers. States also updated the standards used to review and approve programs by transitioning from examining inputs (like faculty qualifications or program resources) to examining how prospective teachers perform while in the program.

As for using data effectively, participating NTEP states recognize the importance of measuring new teachers’ effectiveness. But CCSSO also found that state data systems are woefully underdeveloped, and that in many cases, the quality and relevance of collected data are sorely lacking. NTEP states overcame these obstacles by auditing data that were already being collected in order to ensure that it was shared with other agencies and programs; building and implementing improved data systems; providing data-related training to state and institutional staff; and building data-based rating systems for preparation programs. California, for example, uses its statewide teacher preparation data system to create public dashboards that show how a program’s graduates score on assessments as well as the results of district surveys about newly hired teachers’ performance.

Finally, although NTEP focused on state policy, several higher education institutions within states made significant changes in order to transform the way they prepare their candidates. Clemson University, for example, plans to offer a combined bachelor’s-master’s degree path with an embedded teacher residency program. Similarly, Missouri State University’s College of Education created an internship program that replaced the traditional twelve weeks of student teaching with a yearlong co-teaching model.

For states that are interested in making advancements with their teacher preparation programs and policies, this report serves as a good jumping off point.

SOURCE: “Transforming Educator Preparation: Lessons Learned from Leading States,” The Council of Chief State School Officers (September 2017).

As we’ve come to learn more about sleep and how it affects adolescents, school start times (SST) have become part of a national conversation. Several studies published in prestigious outlets such as the American Economic Journal and Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine indicate that later SST could be beneficial for students, as insufficient sleep is associated with poor academic performance, increased automobile crash mortality, obesity, and depression. And as more benefits of sleep have come to light, several medical organizations, such as the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, have recommended that middle and high schools shouldn’t start until 8:30 a.m. However, understandable concerns about pushing back SST remain, largely regarding increased transportation costs and whether the shift might negatively affect after-school extracurricular activities and employment opportunities.

Enter RAND Europe and the RAND Corporation, which conducted a recent study in which they aim to gauge whether the benefits of later SST are worth the costs. Throughout the process, they sought to address two questions: If there were universal shifts in SST to 8:30 a.m.—versus the U.S. average start time of 8:03 a.m.—what would the economic impact be? And would that shift be a cost-effective policy measure?

Based on prior studies, the researchers focused principally on the notion that students would reap academic benefits given the opportunity to gain additional sleep in the morning; this includes increased high school graduation and college-matriculation rates that in turn should generate economic gains. They also assumed benefits in decreased mortality based on fewer automobile accidents tied to sleep deprivation. On the cost side of the ledger, the RAND analysts considered increased transportation expenses to accommodate the later SST and infrastructure costs associated with pushing back extracurricular start times (e.g., installing lights for athletic fields).

Based on their cost-benefit calculations, the RAND analysts predicted that universally delaying school start times to 8:30 a.m. would be a cost-effective policy. On a national scale, they estimated that after as little as two years, there could be a significant return on investment—an economic gain of about $8.6 billion to the U.S. economy. After ten years, the researchers predicted that the later SST policy would contribute a cumulative $83 billion to the economy. In per-student terms, the analysts predicted a $346 benefit two years after the policy change and $3,309 after ten years. State-by-state estimates were also provided, with RAND forecasting in Ohio a $410 and $3,510 benefit per student after two and ten years, respectively. These net benefits assumed what the RAND analysts consider “normal” costs associated with the policy shift (a $150 per student bump in transportation costs and upfront infrastructure costs of $110,000 per school). However, under higher cost assumptions, RAND analysts estimated diminished returns that don’t actually turn positive for quite some time. For instance, in the higher cost simulations, the payoff of later SST in many states doesn’t turn positive until ten years after the policy change.

This study suggests that it’s worth it to modestly delay start times. Of course, their findings hinge on assumptions about the aggravation and costs associated with changing school schedules. But in practice, schools across the country and here in Ohio (traditional public and charter alike) are indeed making this shift, likely in the hopes of increasing the odds of students arriving to school safely and improving their readiness to learn from the moment they step through their school’s doors. These schools seem to recognize that the old phrase, “you snooze, you lose” might not be correct after all. We shall see.

SOURCE: Marco Hafner, Martin Stepanek, Wendy M. Troxel, “Later school start times in the U.S.: An economic analysis,” RAND Europe (2017).

The teachers and administrators at Columbus Collegiate Academy-Main Street have a strong track record of supporting their students in closing the achievement gap and putting them on a college prep path. CCA-Main students have consistently out-performed their peers in more affluent schools, and eighth graders regularly gain acceptance to the top high schools in Columbus. The United Schools Network, the school’s operator, and its recently launched School Performance Institute, want to share their recipe for success with you.

On November 30, 2017, USN’s Chief Learning Officer John A. Dues will host a day-long Study the Network™ workshop at the school to observe how its culture has been purposefully designed to get results in a high-poverty context. Participants will also discuss how to apply these ideas in their own schools.

If you are interested in concrete steps you can take to help low-income students achieve and thrive academically, this workshop is for you. Registration includes breakfast, lunch, and all necessary materials.

You can find out more information about workshop details and register to attend by clicking here.

It’s one of those perennial ideas in education reform that never seems to get across the finish line: raising the standards for who can teach in our schools. Advocates on the left and right argue that if we could emulate the highest-achieving nations and recruit from the top of our college classes instead of the middle or the bottom, we’d see higher achievement too. (We could also cut lots of red tape and focus on empowering talented educators to make more key decisions.)

To its credit, Ohio has already revamped its licensure system in an attempt to raise the bar. (For more on how the system works, see here.) Ohio’s teacher residency program is a key part of this structure. Beginning teachers must take part in the four-year residency program. The program offers new teachers mentorship, collaboration with veteran educators, professional development, and feedback. It also includes the Resident Educator Summative Assessment (RESA), which requires teachers to electronically submit a portfolio that demonstrates their teaching abilities based on the Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession. In order to earn a renewable professional license, beginning teachers must pass RESA and complete four years in the residency program.

As I noted in a previous analysis, the program and its assessment have drawn mixed reviews. Most of the criticism has centered on RESA, which has been accused of being too cumbersome and failing to provide immediate, direct, and specific feedback. Complaints about the assessment were strong enough that the entire program was nearly eliminated during the most recent state budget cycle.

Thankfully, that didn’t come to pass. But in response to concerns, RESA’s designers did revise the assessment. Here’s a look at three of the most impactful changes to RESA, as discussed in its updated guidebook.

1. What resident educators must do

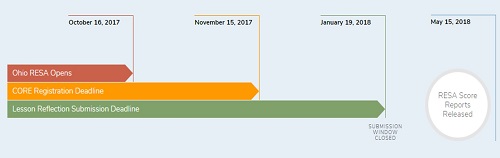

The most obvious change is the number of tasks that resident educators must complete. Last year’s version of the RESA consisted of four separate tasks: 1) first lesson cycle task, which includes the submission of a classroom video 2) communication and professional growth task 3) second lesson cycle task, which includes a second classroom video submission 4) formative and summative assessment task. As you can see from the submission timeline below, the deadlines for these tasks were spread out over the course of the year.

This year’s RESA, on the other hand, requires only one task: the lesson reflection. The updated submission timeline looks like this:

The drop from four tasks to one is an obvious decrease in the amount of work required of resident educators. But to get a better picture of just how significant the change is, it’s worth investigating the dramatic reduction in what teachers are required to submit. According to the 2016-17 RESA guidebook (no longer available online), resident educators were required to submit seventeen different forms, two separate classroom videos for observation purposes, and multiple and varying types of classroom evidence (like examples of communication with parents and caregivers). These submissions were evaluated using upwards of twenty-eight different rubrics, with some submissions being evaluated on the same rubric more than once. Compare those numbers to the new RESA framework, where the Lesson Reflection task includes the submission of only two forms and one classroom video for observation purposes.

2. How resident educators are graded

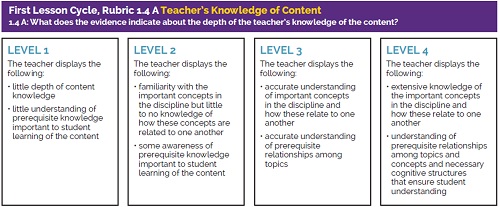

The revised RESA changes not only what teachers must do, but also how they are graded. According to the 2016-17 RESA guidebook, here’s the way a teacher’s content knowledge was evaluated based on a video recorded lesson for the first lesson cycle:

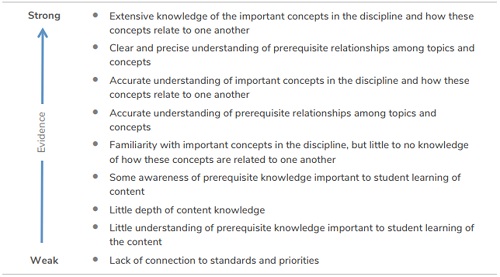

Compare that to the way a teacher’s content knowledge is evaluated on the revised RESA:

There is an obvious difference in structure between the two. But if you look closely, the actual descriptions of a teacher’s abilities haven’t changed—all that’s changed is how these descriptions are arranged. Rather than a rubric that places teachers into specific buckets, teachers will now be placed on an evidence continuum.

The continuum is arguably a better representation of performance, since it more clearly acknowledges that there might only be a very small difference between two teachers previously labeled level two and level three. But how teachers will be graded along this continuum isn’t totally clear.

Unfortunately, there are also still a ton of key details missing that would have been helpful for beginning teachers. For instance, how does a teacher adequately demonstrate a “clear and precise understanding of prerequisite relationships among topics and concepts”? What does that look like for a fourth-grade science class versus a ninth-grade literature class? Sure, it’s a lot more work to give solid examples of each type of evidence, but it could also be profoundly helpful for those taking the assessment. Teachers are taught to give their students exemplars—it seems like a missed opportunity for RESA not to do the same.

3. How resident educators receive their grades

Under previous versions of RESA, resident educators received their score reports on June 1—close to, if not after, the last day of school. Because score reports were delivered so late in the year, many teachers didn’t have the opportunity to discuss their results and next steps with their mentors. The original score reports also contained a limited amount of feedback. Many teachers argued that the limited feedback was unhelpful, particularly in light of the fact that RESA was designed to help beginning teachers analyze and reflect on their own practice.

The new score reports will be delivered to resident educators by May 15, which should provide more time for teachers to discuss their scores with their mentors. These reports will purportedly provide more comprehensive, concrete feedback that teachers can then use to improve their practice. Until this year’s crop of resident educators gets their actual score reports back, it’s impossible to know whether the feedback really is more helpful. Nevertheless, it’s a step forward that the problems with feedback have been recognized and attempts are being undertaken to course correct.

***

Only time will tell if the revised RESA is a better tool for novice teachers and those who are charged with their development. The Ohio Department of Education and RESA’s designers deserve credit for listening to feedback of those who are impacted by its administration and results and making modifications to the assessment. But as with any policy shift, it’s important that policymakers and stakeholders keep a close eye on the changes going forward.

RESA should absolutely give quality feedback to beginning teachers and be streamlined enough that it is not burdensome. But as part of the teacher licensure system, it must also continue to hold a high performance bar for those who educate Ohio’s students. After all, it’s their educational success that hinges on how effective their teachers are.

I recently visited United Preparatory Academy (UPrep). It’s a charter school serving students in grades K-4 (growing to grade five) located in Franklinton—one of Columbus’s poorest neighborhoods, where the median household income is thirty percent lower than the city-wide average. About half the population has less than a high school diploma, and just one in ten have earned a four-year college degree. I say all this not to reduce the neighborhood, its families, or its children to these data points—but because from a research point of view, it makes what I’m about to tell you all the more powerful.

Before the visit started, I sat in the office alongside children who’d been dropped off wearing a random assortment of clothes other than the school uniform. It became apparent that it was a struggle for some families to keep freshly laundered clothes in stock for their children. This challenge is part of a growing conversation about how high-poverty schools go beyond the classroom in order to serve families, and more specifically, curb truancy. About ten kids waited while the office manager reached into a cabinet filled with black dress pants and bright blue, logoed polo shirts. One by one, he held up clothes next to each kid, approximated what might fit (few kids knew their own sizes), then sent them into a nearby restroom to change.

Each child emerged in crisp, clean uniforms, a few with pants needing to be rolled up or shoes to be tied, a few mentioning they had had growling bellies. They went off to their classrooms for breakfast, homework checks, and morning routines while the office manager assessed the clothing supply for that week and noted that it was hard to keep certain sizes in stock.

No matter how often I discuss the statistics, describing a school as “100 percent economically disadvantaged” in the context of research, my perspective changes each time I see its day-to-day impact in person. I take for granted my in-home access to a washer and dryer, even grumbling occasionally about having to do more and more laundry as my children grow. It was a disconnect that I hadn’t fully grasped until that very moment at 8:30 on a random Monday morning after having dropped off my own daughter at school (in uniform).

But this is just part of the story: UPrep’s students are poor, yes. But their academic performance is nothing short of outstanding, even as the school draws in one-third less funding than its traditional public school counterparts.

Not only does UPrep care for the basic needs of their students—things like providing proper school attire or hot breakfasts—they also keep their focus on the basic purpose of school: challenging their students to reach high academic goals.

Because of these efforts, and no doubt because of students’ innate drive to learn and to thrive, they’re knocking it out of the park. The school’s students are passing the state’s third-grade reading guarantee—a measure to ensure that youngsters are reading proficiently before promotion into the fourth grade—at a higher rate than my zoned neighborhood school in Clintonville, one with mixed incomes but also half-a-million dollar homes. Even more impressive is that UPrep third-graders scored accelerated and advanced on state exams at a rate that exceeded the state average and more than doubled that of Columbus City Schools. The table below shows that over half of UPrep third-graders met these lofty achievement levels.

Percent of third-graders reaching accelerated & advanced levels of proficiency (2016-17)

[[{"fid":"119389","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default"}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

What UPrep and its charter network (United Schools Network) are doing is closing achievement gaps—those insidious, long-standing differences in performance between black, brown, and poor children and their wealthier, white peers. Teachers are putting in the gruelingly hard work of educating students who come to them academically behind while also caring deeply about their non-academic needs. Simply put, it’s not an either/or situation: Schools can, and should, do both.

Remember this the next time you hear someone say that Ohio’s expectations regarding third-grade reading are unreasonable, or each time well-intentioned leaders or school administrators try to lower the bar despite knowing full well that the ability to read effectively by third grade is highly predictive of later life success.

Be wary any time you overhear a neighbor, or god-forbid a public school teacher, raise the question, “how can we expect ‘these’ children to be reading at that level by that age?” or suggest that social promotion is the most compassionate option. If they don’t believe their own darling children are capable of so little, you’re looking straight in the face of “the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Excellent schools can and do make a difference for children in poverty. Schools like UPrep remind us just how capable all children are of learning to high levels when we believe that they are and we do everything in our power to support them.