Editor’s Note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Author’s Note: The School Performance Institute, of which I am the Director of Improvement, is the learning and improvement arm of United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. This essay is part of its Learning to Improve blog series, which typically discusses issues related to building the capacity to do improvement science in schools while working on an important problem of practice. However, in the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing how the United Schools Network (USN) is responding to and planning educational services for our students during the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures.

As we are all aware, the COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered how our society has functioned over the past few months. The education sector is no exception. As science teachers can attest, one of the unfortunate, enduring realities for life on this planet is that a minuscule virus, just microns in diameter, can leave an outsized impact on life as we know it. Yet a second enduring reality is that the form of life known as Homo sapiens is awfully resilient, and educators across the country are thinking creatively to ensure continuity of education for our students in a remote setting. One of our most pressing challenges is engaging our students and families in remote learning, a fundamentally different system than the brick-and-mortar landscape to which we’re accustomed. Yet that brings us to a core question: How exactly do we define student engagement in the era of remote learning?

Even in “normal” times, student engagement is defined in a wide variety of ways. Does engagement equate to student participation in a class discussion or raising their hand a certain number of times? Does it mean completing a specific lesson component, submitting independent work, or acing the exit ticket? Or is it simply looking in the teacher’s general direction for the duration of class? Clearly, there are a plethora of ways to define engagement, and the challenge of defining it is only exacerbated in a remote-learning setting. For those of us used to having our students within arm’s reach—looking over shoulders at work, reading body language, reviewing written responses, tracking drifting eyes, responding to the positive energy of hands in the air—defining engagement is hard!

Yet defining engagement in the remote learning setting is as important as it is challenging. Imagine that you are a school leader crafting an entirely new system of instructional delivery, and weeks later, you start getting reports of “Last week, we had 87 percent engagement.” Or, “We currently have 63 percent of our students engaged in online instruction.” How would you react? You may look for the low percentages and hold a conference with the applicable grade levels or teachers. Or you may say “great job!” to the teachers or grade levels with high engagement percentages. However, before you begin evaluating the data, you must ensure that engagement is defined consistently. If the teacher with 87 percent engagement simply counts logging onto Google Classroom as engagement, is that really “great” engagement? Similarly, if the teacher with 63 percent engagement counts a student as engaged if they complete the independent practice component of the lesson with clear evidence of thought, is that really so bad? The point is this: Until you establish operational definitions for core components of remote learning, it is impossible to complete thoughtful analysis and reflection.

One way to create these operational definitions is to utilize the wisdom of W. Edwards Deming and his System of Profound Knowledge, which has four components of thought that are highly interdependent: appreciation for a system, knowledge of variation, theory of knowledge, and psychology. Organizations can use this to create a single, unified way of measuring the extent to which students who are learning remotely are engaged in their lessons and work.

The United School Network (and I state this with deep empathy, as, like all schools, we had to get plans together incredibly fast) was defining student engagement differently across its four campuses. Using Deming’s system, and after many discussions, we landed on distinct definitions for and elementary and middle schools.

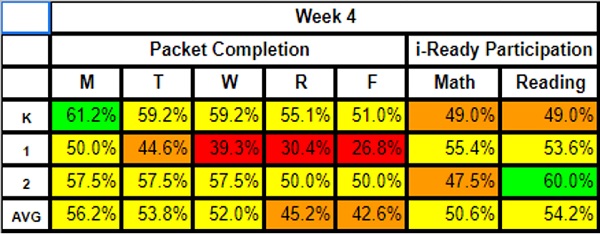

- Elementary: A USN elementary school student demonstrates engagement in a remote lesson by completing the assigned packet pages and sending a photo or other form of evidence that the assignment was completed. Teachers then track the completion of these assignments in engagement trackers and mark them as complete, missing, excuse provided, or needs assistance. In addition, teachers in grades three through five may post the same packet pages in Edulastic as an additional way for students to complete work online.

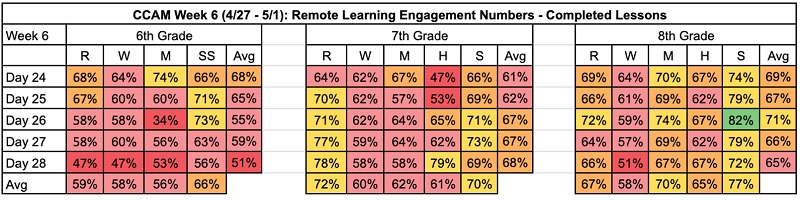

- Middle: A USN middle school student demonstrates engagement in a remote lesson by completing the accompanying practice set in its entirety. Teachers should address student’s accuracy and effort issues through the mechanisms used for providing feedback.

We may have to modify these definitions as we learn more. But for now, they function as a consistent way of thinking about student engagement across campuses and across our network.

The next step was creating a way to measure engagement, which we did by creating separate trackers for elementary and middle school. This lets us analyze data in an informed way—which is the difference between information (“59 percent engagement. Meaning...what?”) and knowledge (“59 percent engagement, meaning that proportion of my students completed the practice set in its entirety last week.”). The gap between the two is everything when you are establishing a new system like remote learning and trying to improve it. Doing this well means our network leaders, school leaders, and teachers all know exactly how to interpret our student engagement data.

Elementary Example

Middle School Example

This spring is flying by, and soon this unique academic year will be over. However, it appears that a complete return to normalcy next school year is unlikely, so we may find ourselves in the business of remote learning for a while. If that is the case, it is vital for us in the education sector to define core remote learning concepts like student engagement. This will allow our students, families, and teams to have clear expectations, to intelligently analyze our data across grade levels and schools, and to easily see where improvement is necessary. All this will ensure that our most struggling students get the informed support they need.

***

This post has focused on how establishing consistent, unified operational definitions of important concepts like student engagement can help school systems and networks establish effective remote learning systems. It was informed by W. Edwards Deming’s theory of knowledge, which is part of his System of Profound Knowledge. In my next blog post, I will focus on how another component of Deming’s system—the importance of possessing a knowledge of variation—can also help improve remote learning. Stay tuned.

Ben Pacht is the Director of Improvement of the School Performance Institute. The School Performance Institute is the learning and improvement arm of the United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. Send feedback to bpacht@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.