For our full report on student mobility, please visit http://www.edexcellence.net/publications/student-nomads-mobility-in-ohios-schools.html

Introduction

Imagine for a moment you’re a school teacher. For the sake of argument, let’s say that you teach at Southmoor Middle School, located on the south side of Columbus. To start your year, you have 25 of Columbus’ most eager, bright-eyed sixth graders in your classroom. Their enthusiasm is fresh like a new textbook and bubbles like a science fair volcano.

Fast forward to May and your classroom has changed considerably. During the school year (you have an average Southmoor classroom) five new students came to your class while eight students departed at some point for another school. For incoming students, you had to make mid-year assessments of those students’ learning levels and quickly integrate them into your lesson plans and classroom culture. You likely did all this without the assistance of a student record (as those can take months to find their way to you), while also maintaining the pace of learning for those students who have been with you all year. Student mobility complicates things.

Pioneering Research

The nomadic-like nature of the Southmoor Middle School student body is not an outlier when it comes to student mobility. In fact, it’s one of many schools in Ohio—and across the nation—that copes with a revolving door of students—students who enter and leave a school during the year.

Student mobility complicates things

Yet, despite the scale and scope of student mobility, the research on it is slim; as far as we could tell, no research has systematically examined the scale of student mobility across an entire state.

Recognizing the cavernous void in student mobility research, along with hearing anecdotes about mobility’s significant impact on some Ohio schools, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute gained an interest in documenting and understanding the scale and impact of mobility. We made our first forays into student mobility in 2010 by partnering with a University of Dayton economist to study mobility in the Dayton area using data provided by the Ohio Department of Education. The findings from that county-wide study were astonishing, showing the magnitude of mobility within Dayton Public Schools, across district and charter schools, and across district lines.

From this limited study we decided that conducting a statewide analysis of student mobility had a lot of merit, but finding an organization that could manage such a massive research project was not an easy thing to do. Serendipitously and out of the blue, we received a phone call from Roberta Garber at Community Research Partners (CRP) expressing interest in working together on some sort of mobility project. CRP had conducted a mobility study for the Columbus City School district in 2003, and had the analytical capacity to do a statewide mobility study. It was a natural partnership.

Thus, the Fordham Institute, Community Research Partners, and ten other funding partners joined together to launch this groundbreaking research project that uses student-level data (over 6 million student records) to gauge the mobility of students across all of Ohio’s 3,500 plus public (district and charter) school buildings and e-schools. Relying on the state department’s Education Management Information System (EMIS) database from two school years (October 2009 to May 2011) we looked at every K-12 school move across the Buckeye State. But, CRP went further, and did a deep dive in five metro areas – Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo, as well as into the state’s major e-schools. The results of this year-long study are significant, wide-ranging, and absolutely foundational for a better understanding of how Ohio’s educational system functions (or dis-functions) in the face of significant numbers of student moves and movers.

Measuring Mobility

School moves for students have many causes. Some are bad – family turmoil, home foreclosure, apartment eviction. Others are good – search for a higher performing school or a school better suited to the needs of a child, a new home in a better neighborhood, or a better job for a parent. Research so far, and this includes the CRP work, cannot easily distinguish the cause of a student move. We can, however, identify those schools that have more coming and going of students. Two indicators measure a district’s or building’s mobility: The two-year stability rate and the one-year churn rate.

For some schools, only 1 in 2 students stay in the same school over two years

- Stability rate – indicates the percentage of a school’s students that stayed in a school from October 2009 to May 2011.

- Churn rate – indicates the incidence of mobility (the number of student admits plus withdrawals), relative the enrollment size of a school, over a single school year (October 2010 to May 2011).

Prevalence of Student Mobility

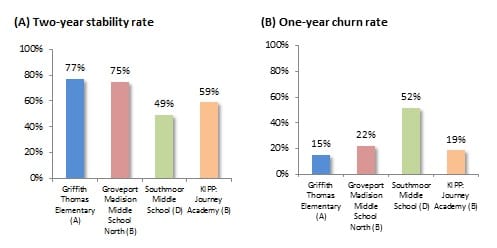

The statewide research conducted by CRP found that the prevalence of student mobility is considerably greater than most of us appreciate or fully understand. Student mobility verges on the epidemic in inner-city schools; but, it is also common in suburbs and rural schools. Figure 1 depicts the stability and churn rates of a few select school buildings in the Columbus region (suburban and urban), including Southmoor Middle School, which led our discussion.

Figure 1: Stability and churn rates for select sample of Columbus-area schools

(A) Stability rate: One quarter (Griffith) to one half of students (Southmoor) leave their original school over two year period. (B) Churn rate: Average class of 25 students would expect to have between 4 (Griffith, 25*.15) and 13 (Southmoor, 25*.52) incidents of mobility in one school year.

Source: Ohio Department of Education, EMIS database, and CRP analysis. Note: Letters in parentheses represent school building rating, school year 2010-11. Griffith Thomas is part of Dublin School District (suburban, high-income); Groveport Madison Middle is part of Groveport Madison School District (suburban, middle-income); Southmoor Middle is part of Columbus City Schools (urban, low-income); KIPP: Journey Academy is a charter school (urban, low-income).

A higher stability rate means that more students stay at the school over time—hence, we’d consider Griffith Thomas, a high-wealth suburban school, to be more stable than Southmoor Middle, though even Griffith lost nearly one quarter of its students over two years. A Southmoor Middle School student experiences more movement of peers, with only one in two students staying in the school over a two year period.

A higher churn rate means that there is a greater flow of students moving into and out of the school. To interpret the churn percentage, we could think of it this way (as we do in our article’s opening paragraph): For a 25-student Southmoor Middle classroom, the average teacher would have had to cope with 13 student arrivals or departures during the 2010-11 school year.

The Impact of Student Mobility on Academic Performance

Persistently mobile students do less well in school than their non-moving peers. We asked CRP to document this for us by connecting mobility history to student test scores. CRP found that frequent school movers face a general downward trend in average test scores and passage rates. For example, Figure 2 depicts the impact of moves for 3rd and 8th graders in Columbus City Schools on both reading and mathematics tests. All lines trend downward.

Figure 2: Columbus City Schools: Average scores on spring 2011 OAA tests by two-year mobility history

Source: CRP and OSU-Center for Statistical Consulting analysis of ODE enrollment records. Note: Third grade is abbreviated by G3, Eighth grade is abbreviated by G8.

Serially mobile students do less well than their peers, and there is a relationship between mobility rates, student demographics and test scores.

Highly mobile students tend to have lower test scores

Figure 3 depicts the average scores on the spring 2011 third grade math test for selected student groups from Columbus City Schools. Scores were lowest for the economically disadvantaged, Blacks, and multiple movers.

Figure 3: Average scores on third-grade math test by CCS students, spring 2011

Source: CRP and OSU-Center for Statistical Consulting analysis of ODE enrollment records

A disproportionate number of multiple movers were also economically disadvantaged and black. These three characteristics in tandem serve as a sort of perfect demographic trifecta for gauging a life-time of school failure by the time a student leaves third grade.

But Not All is Gloomy

Despite the negative impact on student achievement for serial movers, there is a second type of student mobility that benefits students. This happens when a student moves from a failing school to a higher performing school. When students move to a better school it offers them a better chance at academic success if they stay there. Consider the boost a student gets when they move from an F-rated school to an A-rated school. They are apt to receive better instruction, learn in a more secure and healthier school environment, and attend classes with more motivated peers. Any or all of these school-based factors can help drive up the success rates of disadvantaged students.

The silver lining: Some students move to higher rated schools

This mobility study indicates that there is a considerable amount of upward student mobility in the Buckeye State. Consider, for example, the number per students moving from failing urban public schools (D or F rated) to more successful suburban schools (A or B rated schools) in metro Columbus. Of the 5,473 students over two years who exited Columbus City Schools (CCS) for another district, 52 percent moved to a school with a performance rating at least two ratings higher than their CCS school of origin. The percentages where similar for Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton and Toledo and it shows us that many kids across the state are moving to a better situation when they change schools.

Conclusion: Coping with Mobility

We’ve found that student mobility is a near-everyday reality for schools in many parts of the state: Rural, suburban, and urban schools. The CRP research is largely descriptive, and only lightly touches on issues of mobility’s causes and consequences. Let alone the costs or possible advantages of certain types of student mobility. Thus, the findings from CRP, first and foremost, call for more study, public discussion, and debate on all the aspects of student mobility and its impact. Expect more from us on this topic in the coming weeks, months and years as this is an issue that deserves far more study and attention from everyone concerned about Ohio’s children and their schooling.